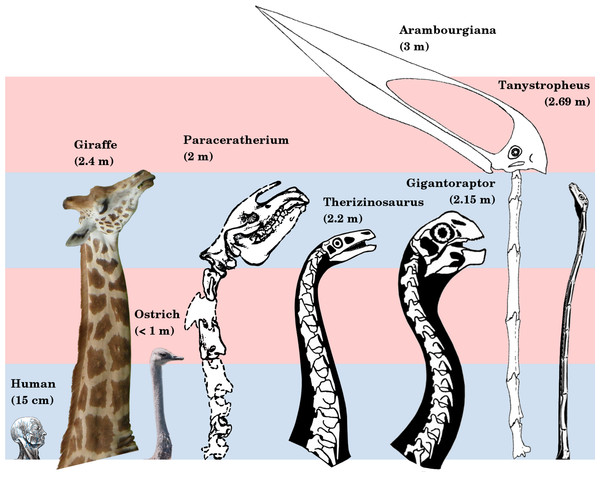

| The 2015 version of the giraffe vs. azhdarchid vs. person image, now in it's fifth iteration (see the general history of these images through the years: 2006; 2007; 2009). The giraffe is a big bull Masai individual, standing a healthy 5.6 m tall, close to the maximum known Masai giraffe height. The pterosaur is a 10 m wingspan Arambourgiania philadelphiae (for reasons I cannot go into now, it is not wise to consider the appearance of giant azhdarchid taxa interchangeable any more: this should not be considered Hatzegopteryx thambema or Quetzalcoatlus northropi). The Disaknowlegement provides the human touch. These characters will receive some additional company soon. |

They nearly weren't called 'azhdarchids'

'Azhdarchidae' is a terrific name. It's short but mysterious, relatively easy to spell, and PR friendly enough that even the British tabloid The Sun has used the term on at least two (I think) occasions. The name 'Azhdarchinae' was coined by the late Lev Alexandrovich Nesov in 1984 from the Uzbek word 'azhdarkho', a name for a mythical dragon, and also the nomenclatural basis for the medium-sized Uzbek azhdarchid Azhdarcho lancicollis. Nesov's name encompassed all three azhdarchid genera known at that time: Azhdarcho, Titanopteryx (now known as Armabourgiania) and Quetzalcoatlus. Almost simultaneously, however, the exact same set of taxa was being roped into another group by Kevin Padian, which he termed Titanopterygiidae after, obviously, Titanopteryx. Nesov's 'Azhdarchinae' pipped the far-less elegant Titanopterygiidae to the publishing punch by a matter of months, and took nomenclatural priority for the group. Padian elevated Azhdarchinae to 'family' level in a short note in 1986, giving us our now familiar term, 'Azhdarchidae'.

|

| Lev Alexandrovich Nesov holds the fossil cervical vertebra, notarium and jaw tip of the azhdarchid Azhdarcho. Image from Unwin (2005). |

Despite their giraffian proportions, giant azhdarchid torso were relatively tiny. Witton and Habib (2010) noted that, like many pterodactyloid pterosaurs, their torsos were probably only a third or so longer than their humeri, suggesting a shoulder-hip length of about 65-75 cm for an animal with a 10 m wingspan. That's a torso length not much larger than your own, although they were considerably more stocky and swamped with muscle. Azhdarchid shoulders, in particular, are well endowed with attachment sites for flight muscles, as are (for pterosaurs) their pelves and hindquarters.

Giant azhdarchids did not suffer from flight power shortages

Many internet commenters often roll out the idea that giant azhdarchids would struggle to take off from the ground, even allowing for new ideas like quadrupedal launching. These folks need to get out of their armchairs, however, and check out some classic work on animal flight and giant pterosaur takeoff. James Marden's 1994 work on animal takeoff found some surprisingly consistent scaling trends among animal flight power and takeoff ability, allowing us to predict the muscle power of even long extinct fliers like Meganeura, Archaeopteryx and a 10 m span azhdarchid. The resulting aerobic power output of azhdarchid flight muscles - all 60 kg of them (a fairly safe bet for a 250 kg azhdarchid given what we know of animal flight muscle fractions among modern fliers) - is a bit rubbish, only 4.52 N/kg of body weight. Animals need to be generating 9.8 N/kg to fight gravity, so this would seemingly ground our giants. Bear in mind, however, that swans, albatross, vultures and turkeys also have aerobic power outputs of around 4.5 N/kg from their flight muscles, and they can fly just fine. The secret to their takeoff lies in the great power of anaerobic muscle contraction, which provides twice the power achieved under aerobic regimes. Using anaerobic power, giant azhdarchid power outputs are 10.098 N/kg of body weight, a value surpassing the 9.8 N/kg and matching the anaerobic power outputs of a 10 kg swan or 1 kg vulture (see graph, below). In terms of power availability, then, giant azhdarchids would not have struggled to launch any more than a large bird, so all these suggestions about poor takeoff ability and whatnot can be put to bed.

Azhdarchids are undeniably best known from Upper Cretaceous rocks, but they also have a patchy and sometimes controversial Lower Cretaceous record. Recently, Gareth Dyke and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that the group were probably present at the very base of the Cretaceous, in Berriasian (c. 140-145 Ma) deposits of Romania. Given that azhdarchids are definitely present at the final stage of the Cretaceous, this gives the group a stratigraphic record spanning the entire Cretaceous: 80 million years in total. This is longer than any other pterosaur group. Two cervical vertebrae from the Late Jurassic of Africa may extend their temporal range another 5 million years, although the affinity of these specimens remains controversial.

When we describe azhdarchids, we often use two qualifiers: 'toothless' and 'long-necked'. In fact, these pterosaurs are brimming with characterising features (above). Their rostra are particularly elongate compared to all other pterosaurs, their orbits are depressed well into the lower half of their skulls, their wing metacarpals and femora are atypically long, and their extremities are short and robust. Their mid-series cervical vertebrae are famously simplified into almost tube-like structures, and their humeri are deceptively derived from the pterodactyloid norm. The wing fingers of azhdarchids occupy a relatively small 47% of their wing lengths, a value only approximated by one other pterosaur group, the closely related thalassodromids. Artists, take note: grounded azhdarchids should not be reconstructed with their folded wing fingers stretching skywards over their backs: they couldn't reach that far.

But no, seriously, the long necks

The cervical vertebrae of giant azhdarchids are poorly known, with only a few specimens (and even fewer good ones) being recovered to date. These rare fossils do, however, clearly indicate substantial neck proportions in at least animals like Arambourgiania. The holotype cervical V of this animal is around 660 mm long, and is missing an estimated 100 mm from its posterior end. Steel et al. (1997) scaled this vertebra isometrically with relatively complete neck skeleton material from the 4.7 m wingspan azhdarchid Quetzalcoatlus sp. to predict a whopping 3071 mm length for cervicals III-IX in Arambourgiania. The use of isometry here is questionable (Witton and Habib 2010), but is defensible given the amount of azhdarchid neck material available to these authors in the mid-nineties. Ongoing work I'm involved with (which will hopefully be published before we're too much older) has attempted to apply allometry to calculations of giant azhdarchid neck lengths. The results are a little more conservative than the 3 m offered here, but we're still landing in the "seriously long neck" camp. Whether azhdarchids will retain the title of absolutely longest necks outside of Sauropoda (Taylor and Wedel 2013) remains to be seen however: I suspect they may ultimately just be pipped by the weirdo protorosaur Tanystropheus. Dammit.

|

| The 'Big Necks Which Don't Belong to Sauropods Competition', won by the giant azhdarchid Arambourgiania. From Taylor and Wedel (2013). |

The necks of azhdarchids are not just famous for their size, but are also renowned for their rather inflexible joints. These widely discussed features have been the bane of many azhdarchid lifestyle interpretations (see Witton and Naish 2008 for a review), but actual quantification of their arthrological range has been lacking until recently. This is, in part, because a complete 3D azhdarchid cervical series has been elusive for many years, but Alex Averianov (2013) recently produced a composite digital neck skeleton for Azhdarcho to figure out their range of motion. The results were more-or-less what we all expected: very limited range in the mid-series, with most of the mobility limited to the extremes. A surprising amount (but still fairly restricted) range of motion was afforded at the neck base, however. As may be expected, this study is very welcome to those of us interested in the biomechanics and functional anatomy of these animals, and I'm glad to see it.

|

| Averianov's (2013) reconstructed neck arthrology of Azhdarcho lancicollis. That's one stiff neck. |

Swimming piscivores and aerial hawking: genuinely suggested azhdarchid lifestyles

It's well known that most recent 'serious' proposals of azhdarchid lifestyles are things like skim-feeding, terrestrial stalking and wading, but many other, frankly outlandish palaeoecological hypotheses have been thrown at azhdarchids over the years. Lev Nesov perhaps takes home the prize for the most bizarre ideas, proposing in his 1984 paper that azhdarchids could swim to find food (both along the surface and by diving) and pursue 'poorly flying' vertebrates through the air. In the same paper, he also advocates skim-feeding as a probably azhdarchid lifestyle. I remain unsure which part of azhdarchid anatomy indicated to Nesov that these animals had superhero-like abilities to acquire food.

|

| Sauropods give a giant azhdarchid the evils. Seems they don't like being buzzed at close range. |

Although azhdarchids are frequently discussed for their natty terrestrial capability nowadays, it's important to remember than any substantial travelling they had to do was probably performed in the air. Computations of the flight abilities of giant azhdarchids have returned seriously impressive results (Witton and Habib 2010). As mentioned above, azhdarchids likely employed anaerobic power for strenuous flight activities like takeoff and perhaps flapping bursts, and likely relied mostly on thermal soaring and flap-gliding like modern raptors to remain airborne for long periods. Their minimum sink and best glide speeds are steady cruises at 16.3 - 24.9 m/s (58.7 - 89.4 kph) but, if they were in a hurry (such as looking for a source of uplift), speeds of up to 48.3m/s (173 kph) were possible for short durations. We estimated that azhdarchids had about 90 - 120 seconds of anaerobic burst power before tiring, meaning these animals could go from a standing start to - literally - several kilometres away in the space of a few minutes. Yowsers. What's more, the size and bodily resources available to such large creatures permitted tremendous flight times: up to 16,000 km of travelling without resting or foraging were likely possible. That's the equivalent of an animal flying from London to Vegas non-stop, realising it forgot its passport, and then flying home again without touching the ground.

And that's your lot for now, folks. If you want to know more about azhdarchids, be sure to check out my book for a whole chapter about them, which is something like the second biggest entry in the entire thing. Things may go quiet over the next few weeks while I'm away at various conferences, but posting will resume when I get back.

References

- Averianov, A. O. (2013). Reconstruction of the neck of Azhdarcho lancicollis and lifestyle of azhdarchids (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae). Paleontological Journal, 47(2), 203-209.

- Dyke, G. J., Benton, M. J., Posmosanu, E., & Naish, D. (2011). Early Cretaceous (Berriasian) birds and pterosaurs from the Cornet bauxite mine, Romania. Palaeontology, 54(1), 79-95.

- Marden, J. H. (1994). From damselflies to pterosaurs: how burst and sustainable flight performance scale with size. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 266(4), R1077-R1084.

- Nesov, L. A. (1984). Pterosaurs and birds of the Late Cretaceous of Central Asia. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 1, 47-57.

- Padian, K. (1984). A large pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Two Medicine Formation (Campanian) of Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 4(4), 516-524.

- Padian, K. (1986). A taxonomic note on two pterodactyloid families. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 6(3), 289-289.

- Steel, L., Martill, D. M., Kirk, J. R. J., Anders, A., Loveridge, R. F., Frey, E. & Martin, J. G. (1997). Arambourgiania philidelphiae: giant wings in small halls. The Geological Curator, 6, 305-313.

- Taylor, M. P., & Wedel, M. J. (2013). Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks. PeerJ, 1, e36.

- Unwin, D. M. (2005). The pterosaurs from deep time. Pi Press, New York.

- Witton, M. P., & Habib, M. B. (2010). On the size and flight diversity of giant pterosaurs, the use of birds as pterosaur analogues and comments on pterosaur flightlessness. PloS one, 5(11), e13982.

- Witton, M. P., & Naish, D. (2008). A reappraisal of azhdarchid pterosaur functional morphology and paleoecology. PLoS One, 3(5), e2271.