|

| Finally: a modern book devoted to everyone's favourite mid-20th Century Czech palaeoartist, Zdeněk Burian. It's big, it's expensive, and it's amazing. For palaeoart fans, it's an essential purchase. |

As much as I’m a fan of 19th century palaeoart, the 20th Century is where our efforts to reconstruct fossil organisms really take off and stretch their wings. In its early decades, Charles R. Knight led a charge to reinvigorate and re-legitimise palaeoart after enthusiasm for illustrating the life appearance of fossil organisms cooled in the late 19th century. Later, the likes of Gregory S. Paul and Jay Matternes transformed how palaeoart would be executed and valued by scientists. And between these trailblazers lies the career of another palaeoartistic giant, an individual who took Knight’s mantle as the most important palaeoartist of his day and carried it almost until his death in 1981: Zdeněk Burian.

Born of Czech descent in Austria-Hungary in 1905, Burian began his palaeoartistic career in the mid-1930s. Much has been said about Burian over the years and his status as a master of palaeoart is unquestioned. Whether we see him as tag-teaming with Knight to define the second half of a “classic palaeoart” era (Witton 2018) or as the lead of another phase, termed “modern palaeoart" by Manucci and Romano (2023), Burian defined the look of prehistoric animals for many of us born in the 20th century. Already a well-established illustrator before being headhunted for high-profile palaeoart projects, Burian took on his first prehistoric subjects just as Knight's career began winding down, and his prodigious artistic ability and eye for natural history made the young Burian a great and intuitive palaeoartist from the start. Heavy promotion from his collaborators pushed his work into the same space of international recognition once held by his American forerunner. Influencing or simply outright copied by countless other illustrators, Burian remained a leading palaeoartist until the final days of his career. The torch was only passed during the late 1970s when a new generation, armed with new science and palaeoartistic philosophy, changed the rules of restoring extinct animals and — for better or worse, depending on your perspective — introduced new aesthetics and values into the discipline (Lescaze 2017; Witton 2018; Manucci and Romano 2023; Müller et al. 2023).

|

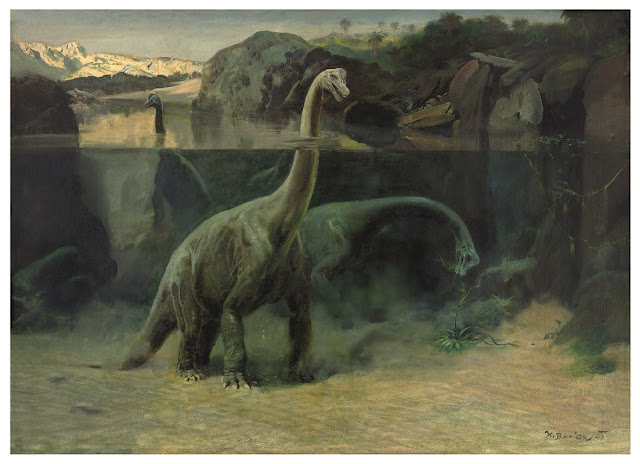

| There are lots of famous images of sauropods from the mid-20th century, but few are as iconic as Burian's 1941 Brachiosaurus. Yes, this scene is impossible but no, that doesn't affect the quality or influence of this image one bit. Borrowed from Albatros Media. |

Given this pedigree, it’s mysterious that Burian’s prehistoric artworks have not been written about as much as those by Knight, Waterhouse Hawkins, or even recent artists like Jay Matternes, at least in the English-speaking world (e.g. Czerkas and Glut 1982; Paul 2000a; Bramwell and Peck 2008; Milner 2012; Carrano and Johnson 2015; Witton and Michel 2022). Take a look at any palaeoart bookshelf and the lack of a decent Burian-themed collection is an obvious and major hole. Until recently, filling this space was only possible by collecting second-hand copies of Burian’s collaborations with Josef Augusta, Zdeněk Spinar and Vratislav Mazák. But with the vintage of these texts reaching or well surpassing 50 years, they are increasingly difficult to find or are prohibitively expensive — rarer Burian texts retail for hundreds of pounds in the UK.

It’s into this void that Albatros Media is injecting their new tome Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1: From the Creation of the Earth to the Extinction of the Dinosaurs (or, in its original Czech, Pravěký svět Zdeňka Buriana - Kniha 1: Od vzniku Země po zánik dinosaurů). Written and compiled by Ondřej Müller, Bořivoj Záruba, Martin Košťák and Rostislav Walica, it represents the first of an ambitious three-part series compiling the totality of Burian’s palaeontological paintings, illustrations and sketches, both familiar and obscure, and many never published before. Available through the Albatros Media website and also select retailers (see below), this first volume may prove to be the most popular as, along with his Precambrian and Palaeozoic artworks, it contains all of Burian’s pre-Cenozoic dinosaur pieces. These, of course, include many unquestionably iconic pieces of palaeoart: water-bound Brachiosaurus (above), blue-green Archaeopteryx, rearing Tarbosaurus and so on. The book is written in Czech and there are reportedly no plans for a full English translation, but English speakers are catered for with some in-book caption details as well as an introductory essay on the Albatros website derived from two important chapters.

Undoubtedly, splitting Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian into three books is the only way to document Burian’s hyper-prolific output. Despite containing just a subset of his prehistoric-themed artwork, this first volume is enormous. Covers measuring 24 x 33 cm sandwich 600 pages of heavy, high-quality paper into a spine almost 6 cm thick. Containing over 400 images, many of which are displayed at large size, the whole package is just a few grams shy of 4 kg. I’ve been tempted to try a patented Tetrapod Zoology Podcast-style table drop to hear the noise of the thud, but I worry about what might happen… to the table. It’s remarkable that another two books, presumably of similar size, will be necessary to document Burian’s palaeontological artwork given that this was not the main focus of his career: he continued to provide illustrations for other books and these, not his extinct animals, form the bulk of his portfolio. I look forward to seeing all three of the palaeo volumes together, even if I am a little concerned about what 12 kg of new books might do to my already creaking bookshelves.

|

| I'm not kidding about that nigh-on 4 kg weight. In future, we'll be able to identify Burian fans by their especially large, well-toned biceps. |

Such size carries a cost: €99 for European buyers (excluding VAT and shipping) and $130 in the US. That aims Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1 squarely at palaeoart diehards and suggests a price tag north of €/$300 for all three volumes. As steep as that might initially seem, it’s actually a bargain compared to the cost of collecting Burian’s art through secondhand book markets. Moreover, with the majority of artworks being rescanned or re-photographed for this project, as well as the inclusion of 135 pieces from private collections, this will be the definitive Burian palaeoart archive for many years to come. Price-conscious buyers may be pleased to know that the illustrations are grouped by geological age rather than by date of production (see below) so you can selectively buy the volume with your favourite time periods or taxa if desired. I suspect there is scope for a coffee table book that compiles the most famous Burian pieces into a more affordable product, but that’s another project, for another time. For now, palaeoart and Burian fans are in for a treat: every penny of that cover cost has gone into making Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1 an exceptional piece of work.

Given that I can’t read Czech, I can only comment briefly on the text via the online introduction and two translated chapters. These cover the outlay of the book, Burian’s palaeoartistic career and his artistic process. Müller et al. (2023) explain their overarching (but not religiously followed) geochronological and systematic arrangement as the best manner to catalogue Burian’s work because he returned to the same subjects, and sometimes even the same compositions, again and again. Displaying his art in order of production may have given a greater perception of Burian’s developing talent and career, but would probably have been confusing and repetitive to read. Instead, we are presented with everything Burian created for different time periods — the complete Burian Archaen, the complete Burian Cambrian etc. — within which artworks are ordered taxonomically. Only here, at this granular level, does Burian’s professional history affect image order, with his oldest takes on a given topic presented first.

This approach makes for an intuitive way to tour Burian’s portfolio and, with a turn of the page, we can compare different eras of his illustrations of the same subjects. We see that his style somewhat tightened over time, the looser qualities of his earliest work turning into more exacting brushstrokes and finer detail by the 1950s. He also revised and repainted many illustrations in light of new science. The latter is an overlooked aspect of Burian’s palaeoartistry because it can, owing to its volume, ubiquitousness and the sometimes subtle alterations he made to older paintings, seem homogenous and largely unchanging when viewed in isolation. But when presented together, we see that Burian’s portfolio is arguably one of the most scientifically transformative of any palaeoartist. In spanning the 1930s to the earliest 1980s, his career captured wholly different, often strongly contrasting palaeontological perspectives. Sometimes viewed as following the “modernist consensus” of dinosaur science (Paul 2000b), Müller et al. (2023) argue that Burian pushed boundaries in dinosaur reconstruction where he could, such as by depicting mobile-wristed and charging ceratopsids as early as the 1940s and 1950s, as well as embracing Bakkerian dinosaur form in the 1970s. I wonder what Burian, who would have been in his 70s when working on these “new look” dinosaurs, thought of producing such radically different takes on subjects after 40 years of creating “traditional”, now old-school reconstructions.

|

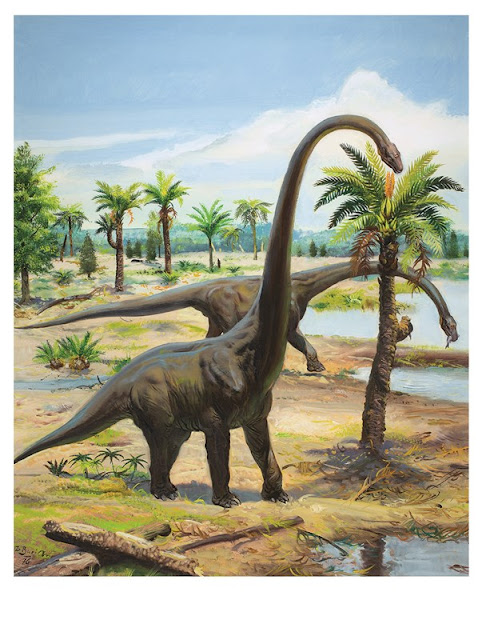

| Burian's 1976 Barosaurus, an example of the "giraffoid Barosaurus" meme started by Bob Bakker. We can criticise this painting for being derivative of Bakker's original but, for 1976, this was still cutting-edge stuff: compare this to the Brachiosaurus above, drawn decades earlier. As noted by Müller et al. (2023), Burian's paintings sometimes borrowed elements from other artists because he lacked access to specimens himself, and had to work pretty much exclusively from secondary sources of paleontological information. Image from Albatros Media. |

Müller et al. (2023) give some fascinating insights and observations on Burian’s career and artwork, both of scientific and cultural nature. Among the most interesting and, to my knowledge, novel, concerns how Burian’s palaeoart served as propaganda. The prominence of his art in the West makes it easy to forget that Burian lived and worked on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain, and Müller et al. (2023) argue that he ultimately benefitted from socialist rule despite the hard times faced by artists in Czechoslovakia during the mid-20th century. A communist coup saw private publishers nationalised in the late 1940s and this put many illustrators out of work, potentially including Burian. But his palaeoartistic collaborations with Josef Augusta were officially supported and encouraged by the new regime because of their embodiment of Darwinism, a philosophy embraced by Marxist-Leninist outlooks. Somewhat ironically, Burian’s own conviction on evolution was not so firm; his take on life's development was open-minded and pantheistic in nature. Regardless, he profited from the capacity of palaeoart to promote ideals important to a socialist government and his illustrator career was not only rescued from ruin, but destined for opportunities among lauded authorities and individuals. Müller et al. (2023) do not go so far as to compare Burian's career with those of other famous palaeoartists (at least, not the in the texts I can read) but it’s hard not to see his professional life as a political mirror of Knight’s, who found his own fame via support from the independently wealthy, thoroughly capitalist benefactors of American museums.

Müller et al. (2023) further comment on Burian’s approach and attitude to art, and their view is a little more complex and nuanced than that offered recently by Zoe Lescaze (2017). Lescaze posits that a troubled upbringing, a strained relationship with his father, a penniless independence at the age of 15 and the near-constant threat of war and political upheaval contributed to what she perceives as a savage, brutal art style. She sees his paintings as being populated by “sinister dinosaurs”, “thuggish Neanderthals” and other “monsters charged with an almost carnal corporeality”. Müller et al. (2023) agree with this to a point but caution against “foreign theorists” stereotyping Burian by interpreting his work as being the product of a politically troubled state. While also finding melancholy in Burian’s lonely, sad-looking dinosaurs and his fragmented hominid family groups, they marry the tinge of sadness and isolation in Burian’s paintings with the more pragmatic, aspirational and upbeat sides of his character. It's noted that his compositions were often shaped by his forensic attention to scientific detail, his desire to teach through his paintings, and an “uncomplicated and playful” worldview that was captivated by nature. This multifaceted interpretation of Burian’s seems more likely to me than the barely-contained savagery suggested by Lescaze, especially because, for all his dozens of scenes of animal confrontations, physical violence is not a feature characterising his artwork. You can thumb all the way through Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1 and find virtually no violence or gore.

|

| Burian's moody Monoclonius. If you asked me to place this in palaeoart history I would have suggested the 1970s or 1980s for its somewhat Stoutian qualities. But no, this is from 1948: Burian was taking palaeoart to strange new places well before the modern push for greater artistic styles and approaches. Another swipe from Albatros Media. |

Of course, one does not really buy a compilation of Zdeněk Burian palaeoart just for the text: what about the presentation of the artwork itself? On this most critical matter, Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1 truly excels. It seems that no expense has been spared in documenting everything Burian created on prehistoric subjects, from preparatory sketches and drawings to paintings and illustrations in all sorts of styles and media. All are reproduced at good sizes and in excellent detail. Short of looking at the actual artworks themselves, it’s hard to imagine getting a better view of his creations. Unsurprisingly, the visualisation is far superior to that of older books and yes, you definitely want these versions for their improved colour balances and detail even if you already have a copy of something like Spinar’s Life Before Man or Augusta’s Prehistoric Animals on your shelf (see direct comparison, above). Look closely and you’ll note that even the surface texture of Burian’s oil pieces is evident. The printed page can’t replicate the actual three-dimensional quality of his paintings with their thick paint ridges or their picked and threadbare, canvas-exposed regions, but you certainly get a sense of their presence. Special mention should be made of the multitude of plans, notes, roughouts and sketches that feature alongside finished pieces. We rarely or only tokenistically document these peripheral but enlightening pieces in our palaeoart literature, so their inclusion is very welcome here.

My only slight gripe with the images concerns layout, as many are stretched across two pages in a way that loses details in the page binding. This is a concern for any book but, in this 6 cm deep monster, the page gutter is a deep chasm, especially if the book is not laid flat on a table. But to mention this is nit-picking of the highest order and I’m ultimately moaning about a design no-win scenario: if seam issues were avoided by consigning images to one page only, I’d probably be asking for bigger pictures.

|

| Preview pages of Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1 compiled from Albatros Media's website. Note the diversity of images: ink drawings, sketches, annotated illustrations and full paintings. |

Indeed, there’s only one real issue with Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1: it’s too good. In this first book alone, Müller et al. (2023) have set the standard for documenting our palaeoart masters so high that other efforts look underwhelming by comparison. If volumes 2 and 3 follow suit, the Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian series will be the gold standard for documenting any palaeoartist, and the fact Ondřej Müller, Bořivoj Záruba, Martin Košťák and Rostislav Walica have achieved this for someone as prolific as Burian is nothing short of a triumph. The amount of care and investment that’s gone into this project is extraordinary and it will take an especially dedicated team to create a palaeoart compilation for another artist that can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with it. And that, for the record, is the new goal: I’m not sure any collection will ever surpass it. Yes, it really is that good.

Prehistoric World of Zdeněk Burian Volume 1: From the Creation of the Earth to the Extinction of the Dinosaurs (Pravěký svět Zdeňka Buriana - Kniha 1: Od vzniku Země po zánik dinosaurů) is out now. It is internationally available from Albatros Media as well as select retailers and distributors, including Donald M. Grant in the US and NHBS in the UK. European buyers can also email burian@albatrosmedia.cz for more information.

Enjoyed this post? Support this blog for $1 a month and get free stuff!

This blog is sponsored through Patreon, the site where you can help artists and authors make a living. If you enjoy my content, please consider donating as little as $1 a month to help fund my work and, in return, you'll get access to my exclusive Patreon content: regular updates on upcoming books, papers, paintings and exhibitions. Plus, you get free stuff - prints, high-quality images for printing, books, competitions - as my way of thanking you for your support. As always, huge thanks to everyone who already sponsors my work!

References

- Bramwell, V., & Peck, R. M. (2008). All in the Bones: a biography of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. Academy of Natural Sciences

- Carrano, M. T. & Johnson, K. R. (2015). Visions of Lost Worlds: The Paleo Art of Jay Matternes. Smithsonian Books.

- Czerkas, S. M., & Glut, D. F. (1982). Dinosaurs, mammoths, and cavemen: the art of Charles R. Knight. Dutton Adult.

- Lescaze, Z. (2017). Paleoart: Visions of the prehistoric past.

- Manucci, F., & Romano, M. (2023). Reviewing the iconography and the central role of ‘paleoart’: four centuries of geo-palaeontological art. Historical Biology, 35(1), 1-48.

- Milner, R. (2012). Charles R. Knight: the artist who saw through time. Abrams.

- Müller, O, Záruba, B, Košťák, M & Walica, R. Rostislav. (2023). Pravěký svět Zdeňka Buriana - Kniha 1: Od vzniku Země po zánik dinosaurů. Albatros Media.

- Paul, G. S. (2000a). The art of Charles R. Knight. In Paul, G. S. (ed). The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. Macmillan. 113-118 pp.

- Paul, G. S. (2000b). A quick history of dinosaur art. In Paul, G. S. (ed). The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. Macmillan. 107-112 pp.

- Witton, M. P. (2018). The Palaeoartist’s Handbook: Reconstructing Extinct Animals in Art. Crowood Press.

- Witton, M. P. & Michel, E. (2022). The art and science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. Crowood Press.

Dammit, Mark, I need the expense like I need (another) hole in the head. I'm going to try to hold off, hanging my hat on my poor comprehension of Czech (by which I mean I can tell if something is in Czech but that's the end of my comprehension). Maybe when I get to August, where I get 3 paychecks (so one is unencumbered by monthy expenses. I will have to be strong and I hate that, so cut it out!

ReplyDeleteThat barosaurus in the background has caught a fish. It's an interesting bit of speculation.

ReplyDelete