So, that’s that. With the release of Jurassic World: Dominion the so-called “Jurassic Era” — which is what certain posters now want us to call the six loosely connected films in the Jurassic Park series — is over. Whether it's actually concluded will surely be determined by box office revenues more than creative necessity but, whatever: for the time being, the Jurassic Park movie series is officially finished.

However we feel about the Jurassic films, we have to acknowledge two facts about them. First, they represent a uniquely successful stream of palaeontology-inspired products. I can’t think of another string of dinosaur movies that have all had theatrical releases, nor has anything dinosaur-related ever generated so many billions of dollars. Once enough time has passed to fully gauge their impact, I’m sure palaeontological historians will give the Jurassic films serious study as a cultural phenomenon that shaped decades of conversations about prehistoric life. Whether we like it or not, 21st Century dinosaur outreach takes place in a big, Jurassic Park-shaped footprint stamped into pop culture.

Second, it’s not controversial to say that the Jurassic series has been critically divisive. Only the 1993 original is regarded as a classic and is widely, deservedly considered to rank alongside Spielberg’s best crowd-pleasers like Jaws and Raiders of the Lost Ark. The Jurassic sequels, on the other hand, have made a lot of money, but fans and critics often clash about which, if any, rank above mediocre. 2015’s Jurassic World is generally regarded as the best sequel, perhaps aided by borrowing much of its plot structure from the original film, but even this has not escaped accusation of thin, contrived plotting and flat, boring characters. This is to say nothing of the series’ slide away from palaeontological science towards increasingly inaccurate, toyetic creature designs.

Moreover, and echoing broader trends in blockbuster cinema, the Jurassic films have also become increasingly action-orientated. This means, relative to the original, they feature many more dinosaur sequences. The new trilogy in particular is stuffed with as many dinosaurs as each film can bear. Box office receipts show that this elevated level of prehistoric mayhem has paid off, as least among general audiences and we can't truly blame the Jurassic filmmakers for adding more dinosaurs: they are, after all, making dinosaur movies. Aren't they just giving us what we want and expect? Maybe, but I suspect this is actually the fault line along which these films divide opinion. If you're the sort of person who punches the air every time a Jurassic film includes a new species, no matter how fleetingly and inconsequentially, you've probably enjoyed the last three films. If, however, you tire quickly of what can be repetitive dinosaur sequences and want a little more in terms of story and characterisation from your Jurassic experience, you're more likely to view this dino-centricity as mindless, dull prehistoric noise.

This raises the question of whether dinosaur films can, perhaps against expectation, go too far with their main draw: can a dinosaur film actually have too many dinosaurs? The answer, of course, is a matter of opinion, but one way we might try to answer it objectively lies in revisiting the only Jurassic film we all agree is genuinely good: the original Jurassic Park. Were these filmmakers all in on dinosaurs, adding as many as their budget and technology would allow, or is the famously low dinosaur screen time of Jurassic Park a creative decision?

Now eventually you plan to have dinosaurs in your dinosaur film, right? Hello? Hello? Yes?

The story behind the script for the first Jurassic film is recounted in Shay and Duncan’s 1993 book The Making of Jurassic Park, and much of the following is taken from that source. The script took a long time to come together, going through several rewrites by different people. Original book author Michael Crichton was contracted to take the first stab at the film's screenplay but admitted that his heart was never in it. Crichton had literally just finished the novel and simply wasn’t interested in adapting the story so quickly after putting his own version to bed. A second treatment was penned by Malia Scotch Marmo, who’d just written Spielberg’s 1991 Peter Pan adventure Hook. Her version is notable for blending the character of Ian Malcolm with that of Alan Grant to give the latter more personality, as the weakly fleshed-out characters of Crichton’s novels were regarded as a problem that needed solving for the film.

|

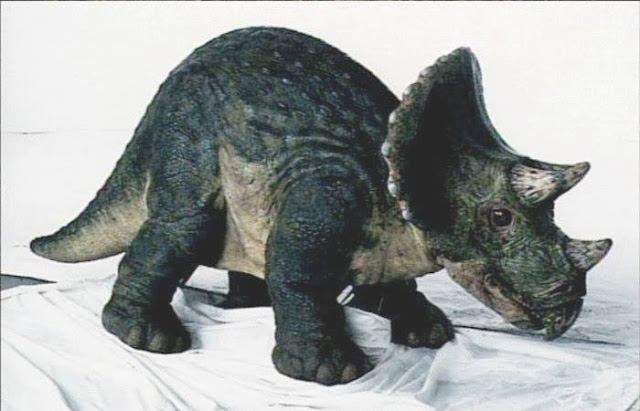

| Photograph of the essentially completed, but never used baby Triceratops built for Jurassic Park. The scene with this animatronic ended up being abandoned for creative reasons, despite the money invested in bringing it to completion. Fans would briefly see this guy in action during a very quick cameo in The Lost World, however. Image from Mike Tharme's Twitter feed. |

But Marmo’s interpretation wasn’t well received either and, relatively close to the start of filming, another writer was hired for a third stab at cracking the story. Enter David Koepp, who you’re surely familiar with from some of the biggest blockbusters of the 1990s and 2000s: Jurassic Park and its first sequel, 1996’s Mission: Impossible, Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man, the 2005 War of the Worlds and… er… Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (hey, I didn’t say they were necessarily good blockbusters). Koepp proved to be the person who could finally tap the full potential of Crichton’s novel, perhaps because he and Spielberg agreed on a major problem with their source material: it had too many dinosaurs. Lest it be thought I’m generalising or paraphrasing, this is exactly how Spielberg described adapting the novel.

“Believe it or not… the first thing I thought was that the book had too many dinosaurs in it. I didn’t think it was physically possible to make a movie that chock-full of dinosaurs… What I wanted to do was boil the book down and choose my seven or eight favourite scenes and base the script around those. So we crunched the book.”

Steven Spielberg, quoted in Shay and Duncan (1993, p. 12)

Given that the first Jurassic Park was pioneering so many new special effects, we might assume that Spielberg’s reservations reflect limitations of technology and budget. But while these were surely limiting factors, they were not the only considerations when it came to losing dinosaur sequences. In fact, we know expensive effects were scrapped after script changes in at least one instance, when a year’s worth of development and production on an animatronic baby Triceratops was abandoned late in pre-production. This effect was intended for a whimsical scene where Lex Murphy would ride around on it, further demonstrating the "dinosaurs were not monsters" ethos etched into the writing and production philosophy of Jurassic Park. But Koepp found the scene interrupted the flow and tone of the film wherever he placed it in the script. As he explained:

“If we put the [Triceratops] ride before the T. rex attack, it slowed down the movie; if we put it after the T. rex attack, why would this kid who has just been attacked by a giant lizard go and ride one?”

David Koepp, quoted in Shay and Duncan (1993, p. 64)

Because Koepp was working on the screenplay at the 11th hour, this decision meant that work on the 1.5 m long baby Triceratops robot was abandoned literally days away from its completion, all so that the film would have a tighter, leaner story. As much as Koepp felt that the audience needed a reminder that dinosaurs were “innocent” animals following the T. rex attack, a child riding a bounding baby Triceratops would have been a tonal shift too far, and certainly out of character for a traumatised child. With this dinosaur scene cut, Koepp added a little more whimsy to the foraging Brachiosaurus sequence, allowing our shell-shocked characters to be reminded that dinosaurs aren't evil or vindictive. They're just animals, as Grant puts it, doing what they do.

|

| Concept art for the Jurassic Park rafting sequence, swiped from the Jurassic Wiki. This doubtless would have been an action-packed scene, but would it have added anything to the film? |

This was not the only planned dinosaur sequence that was cut for pacing and tone. Several parts of the novel that seemed tailor-made for cinema were abandoned, such as Muldoon tranquillising the Tyrannosaurus and the famous river sequence. The latter, where Grant and the kids escape a swimming T. rex in a raft, was included in all previous drafts of the screenplay and went as far as having concept art produced, but Koepp removed it without hesitation. In discussing why, he addresses the “too many dinosaurs” issue directly, noting that Crichton's novel was actually bogged down by its large number of dinosaur episodes. He remarked that “It seemed to me that at certain points in the book we were being taken on sort of an obligatory tour past every dinosaur the park had to offer", such that "the raft trip was rather redundant” (Shay and Duncan 1993, p. 55). Clearly, Koepp didn't consider dinosaurs for the sake of dinosaurs an excuse for their inclusion in Jurassic Park: they had to add something to the film to justify their presence. The result is that dinosaur scenes only constitute about 15 minutes of Jurassic Park’s two-hour runtime. Their off-screen presence drives the film, of course, but almost 90% of the film passes without a dinosaur in shot.

If we turn to literature, we find that this kind of reserved approach to creating a dinosaur story is in good company. Other classic works of "dinosaur" fiction such as Jules Verne’s 1864 Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Conan Doyle’s 1912 The Lost World and Ray Bradbury’s 1955 A Sound of Thunder feature prehistoric animals in memorable sequences but, like the first Jurassic Park movie, these are kept short and impactful. I wonder if this reflects a shared realisation about the narrative potential of fictional prehistoric animals: as initially exciting as they are, they quickly exhaust what they can contribute to a story. Most fictional dinosaurs invariably have to interact with people and their roles are essentially limited to inspiring awe or terror, which means their actions are either peaceful or violent. We can vary where and why these interactions occur, and we may gain additional mileage from featuring different prehistoric species, but it’s difficult not to basically rehash the same ideas and scenes over and over once dinosaurs turn up in a story. And because dinosaurs are real animals, we can’t ascribe crazy, unexpected biology or properties to them, either — not with a straight face, anyway. Jurassic World; Dominion was never going to end the series with a reveal that an evil interdimensional dinosaur was the real villain of the series all along, or show that the dinosaurs were really birthed by an awful, vengeful Megadinosaurus queen. More the pity, perhaps?

Compounding these creative issues for dinosaur films are the huge budgets needed to create dinosaur visual effects. Movie dinosaurs are so costly that their films must appeal to broad, mainstream audiences to be financially viable, and this means avoiding creative choices that will alienate casual viewers, especially children and families. Anything too scientific and “boring” is unlikely to feature, as is anything too violent or horrifying. This, I suspect, is why the Jurassic films are the only game in town for dinosaur motion pictures. Whether humans meet dinosaurs through time travel, in a “lost world” setting or via resurrection from fossils, the Jurassic films are already exploring the full remit of what movie dinosaurs can do. There’s probably not enough creative space for another franchise to present their own, fully distinguished take on dinosaur scenarios, especially given the potential financial losses if such efforts flopped.

Back to the Park

In representing its own contained franchise, the Jurassic series represents a unique case study of attempts to escape these creative restrictions. But it seems fair to say that, even after six instalments, the franchise never really figured out how to get more agency from its reptile stars. Repetition, not innovation, is the order of the day, leading to essentially the same moments playing out in each instalment (as super-seriously scientifically documented by Dave Hone, see his tweet below). Instead of new dinosaur dramas, we simply get more of the same dinosaur scenes. This suggests a creative ethos of, when in doubt, add more dinosaurs!

Got around to seeing Dominion last night thus allowing me to complete my table of Jurassic Park franchise cliches. There were, inevitably, loads. pic.twitter.com/NxvJKm9MLT

— Dr Dave Hone (@Dave_Hone) June 18, 2022

Ramping up the dinosaur content began in the first Jurassic sequels but reached its apogee within the most recent films. Whereas Jurassic Park slowly led us into the world of recreated dinosaurs and established its setting, characters and story before letting dinosaur havoc commence at the one hour mark, the sequels have started their action sequences earlier and earlier. Jurassic World has Velociraptors attacking their handlers after 25 minutes, people are visibly chomped in the first five minutes of Fallen Kingdom, and Dominion is the least patient of all, showing prehistoric animals attacking people within the first minute. And this is where we can start to explore whether an “add more dinosaurs” approach has drawbacks, because all these extra dinosaur scenes absorb time from the fabrics that actually tie films together: stories, characters and themes. And, OK, we might ask who is really watching a dinosaur film for great characters and stories, but we've seen that perfectly serviceable, universally-liked dinosaur films can be done (Jurassic Park) and, moreover, screenwriters should be aiming to have something to hang a film on to give their dinosaur action agency. Putting characters in peril is toothless if we don’t care whether they survive or not. Writing a "dinosaur film" doesn't excuse filmmakers from attempting to make the best, most engaging film they can.

Viewed from this perspective, Fallen Kingdom and Dominion are especially full of what is ultimately pointless dinosaur action, wheeling out prehistoric animals to menace our heroes for a short time (often less than a minute) before moving on to the next, equally pointless encounter. Portions of these films are like riding a dinosaur-themed ghost train where dinosaurs pop out to roar at us before disappearing into the shadows, never to be seen again. And lest it be thought I'm some sort of film snob (I'm not: my benchmark for enjoying most films is how closely they approximate Evil Dead II), the tedium of such scenes was not lost on Steven Spielberg himself, who has candidly spoken of how bored he was making the (relatively) dinosaur-heavy The Lost World:

“I beat myself up…growing more and more impatient with myself… It made me wistful about doing a talking picture because sometimes I got the feeling I was just making this big silent-roar movie… I found myself saying ‘is that all there is? It’s not enough for me.’”

Steven Spielberg, quoted in McBride (2011, p. 455)

It’s hard not to contrast this creative approach and the impact of these dinosaur sequences with those of the first film. Jurassic Park clearly relied on the tried and true creative philosophy of “less is more” and carefully managed its story and tone so that its dinosaur action scenes, once unleashed, were genuinely exciting. But the successive films seem to have embraced a “more is more” approach that prioritises dinosaur violence over anything else. For me, this is one of the main reasons that the Jurassic World series has been such a flatline: the overabundance of dinosaurs roaring and fighting starts to get in the way of the films, actually undermining my enjoyment despite, in theory, adding to the excitement. To give an example, here are six minutes of the Fallen Kingdom volcanic eruption set piece. This takes place, for context, about 35-40 minutes in:

What stands out here is, first; wow, there are heaps of dinosaurs packed into this segment, but second, most are disposable, throwaway additions. The Baryonyx, which is never named, set up or returned to, comes and goes within 90 seconds. Likewise, the Allosaurus menacing the tumbling gyrosphere is there for a moment, and then gone. Clearly, the most important dinosaurs are the stampeding collective: they're what is really driving the action and story at this point, along with the erupting volcano. To give credit where it's due, I actually find the fleeing dinosaurs and eruption pretty engaging (as ridiculous as the galloping ankylosaurs and so are ) and, as our heroes shelter behind a fallen tree being smashed to pieces by charging dinosaurs, I'm curious to see what happens next. But then everything stops... so we can have a quick dinosaur fight scene. No more eruption, no more stampede. All the scene's momentum is discarded so Carnotaurus can slowly stalk around the human characters before getting into a fight with Sinoceratops. Why these dinosaurs are fighting rather than fleeing like all the rest isn't clear, but within seconds none of it matters: the Carnotaurus is put down (killed? I'm not sure) by the passing Tyrannosaurus, which then stops to roar in defiance despite the island literally exploding behind it. The T. rex then leaves, paying no attention to the humans, and the eruption and dinosaur stampede resumes as if someone has thrown a switch offscreen.

Along with killing all momentum, this dinosaur fight is confusing and, uh oh, gets us asking questions about the film. Why weren't these dinosaurs running away? Why didn't the Carnotaurus predate the easily-caught people instead of breaking off to attack a multi-tonne horned dinosaur? Why did the T. rex attack the Carnotaurus and then just walk off? Does T. rex watch Parks and Recreation and wanted to help out Andy Dwyer? Where did all the stampeding dinosaurs go? While the Baryonyx and Allosaurus portions are so superficial and inconsequential that they don't hurt the flow of the film by themselves (if, admittedly, such incessant "dinosaur cameos" of the World films do become repetitive and grating, especially in Dominion), the Carnotaurus sequence totally distracts from what should be our main focus at this part of the film. I guess the logic was that giant reptiles fighting is exciting and will thus make the eruption more engaging, but it actually does the opposite: it sucks energy and drive from the movie. It also presents a problem for story progression because it leaves the film struggling to raise the stakes later on. How do you create a situation more dangerous and exciting than dinosaurs fighting on an exploding island? Doesn’t everything seem a bit flat and dull after that? These additions are so out of place that I strongly suspect they were only added because the film otherwise lacked large theropods fighting, as if that's the only way to put drama into a dinosaur film.

Unrelated clip from Jurassic Park.

The irony in this, of course, is that the World films also revel in nostalgia for the first Jurassic Park, and yet the creative philosophy behind them is almost antithetical to that used by Koepp and Spielberg. In my view, this it shows little understanding of what made the first film great. We talk a lot about how the revolutionary dinosaur effects of Jurassic Park were integral to its success, and how its portrayal of post-Dinosaur Renaissance science blew audiences away. We also acknowledge that Jurassic Park is a rare "lightning in a bottle"-style production, the output of some of the best filmmakers of the early 1990s working at the top of their game. These are all true points, but we should add “creative restraint” to this list of success factors. A “less is more” dinosaur philosophy allowed for a logical, well-paced story with likeable, charismatic characters and truly iconic, memorable dinosaur scenes. It might only be 12% dinosaurs, but that's enough to make their screen time special and satisfying without any risk of it becoming boring or repetitive. This allows the dinosaur sequences to be the emotional high points of the movie, all choreographed perfectly to the developing story. The super-tense mid-movie T. rex attack initiates the start of chaos on the island. The Velociraptor kitchen scene ups the ante as we approach the climax, suddenly throwing the kids — hitherto shielded by adults against danger — against two smart, deadly predators. And the climactic battle between Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus finishes the film with a flourish, saving our heroes at the last moment in the most exciting way possible. These are dinosaur action sequences that build upon one another and drive the story, such that we know, intuitively, where we are in the movie. You needn’t look at your watch to know that the sight of the Tyrannosaurus roaring as the “when dinosaurs ruled the Earth” banner slips past means the film is over. This is blockbuster entertainment done with real craft and care, and it remains the best dinosaur film ever made not despite its lack of dinosaurs, but because of its lack of dinosaurs. It’s no surprise that the World films mine the iconography of Jurassic Park so frequently because, in never taking a break from throwing dinosaurs around, they never established compelling enough stories, characters or moments to create their own iconic elements.

So perhaps, as contradictory as it seems, the Jurassic film series makes a case that dinosaur films can work a lot better when they have fewer dinosaurs or, at least, when dinosaur action isn't prioritised over more fundamental and important components of filmmaking. The problems outlined here are not unique to the Jurassic sequels, of course: we could level the "too many dinosaurs" criticism at plenty of other films, from Peter Jackson’s 2005 King Kong to even the likes of 1966’s One Million Years BC. And I think it's important to add that "too many dinosaurs" doesn't necessarily ruin a film, but they might diminish our enjoyment to greater or lesser extent.

Ultimately the point made here is just a dinosaur-specific reminder that special effects and action alone do not make good films: it's memorable stories, characters and situations that resonate most with critics and audiences alike. So if this really is the end of the Jurassic franchise, let’s hope that the next generation of dinosaur films doesn’t just bring fresh ideas, fresh stories, and fresh palaeontological science to our screens, but that they also reflect on a crucial question for this niche genre. Can dinosaur movies have too many dinosaurs? Well, if you want everyone to enjoy your film, and you want to make a film that will last the ages, then maybe yes, yes they can.

Enjoyed this post? Support this blog for $1 a month and get free stuff!

This blog is sponsored through Patreon, the site where you can help artists and authors make a living. If you enjoy my content, please consider donating as little as $1 a month to help fund my work and, in return, you'll get access to my exclusive Patreon content: regular updates on upcoming books, papers, paintings and exhibitions. Plus, you get free stuff - prints, high-quality images for printing, books, competitions - as my way of thanking you for your support. As always, huge thanks to everyone who already sponsors my work!

References

- McBride, J. (2011). Steven Spielberg: A Biography, 2nd edition. University Press of Mississippi.

- Shay, D., & Duncan, J. (1993). The Making of Jurassic Park. Ballantine Books.