If you're the sort of person who's interested in cool stuff like anatomy, evolution and functional morphology, you can't have missed two incredible books published in recent years by author and artist Katrina van Grouw:

The Unfeathered Bird (2013) and

Unnatural Selection (2018). Although tackling different topics, they are united by their exceptional illustrations of animals in various states of dissection (though mostly skeletonised), lavish design, great production quality and highly detailed yet accessible text.

The Unfeathered Bird, which focuses on bird skeletal anatomy and functional morphology, caused ripples in the palaeontological community upon release for being a book which looks at modern birds the way we look at fossil animals. As a monumental book - huge, comprehensive, scholarly and aesthetically spectacular - I'm sure we would all have been happy with more of the same for Katrina's follow up project (

The Unfuzzy Mammal, The Unscaled Reptile,

The Un... er... skinned Amphibian?) but her latest book,

Unnatural Selection,

is even more ambitious in scope, detailing how human-controlled animal breeding - the titular 'unnatural selection' - offers a window into the mechanics of biological evolution.

|

| Katrina's new book, Unnatural Selection, available now from Princeton University Press, all the usual online retailers and good book shops. |

To celebrate the release of

Unnatural Selection a few months ago, I invited Katrina to give an interview about her new book, her art, and her future projects. I do this as a certified van Grouw fan: the Disacknowledgement and I have three van Grouw artworks on our wall in addition to her books on our shelves. Katrina has always skirted the line between author, scientist and artist and, before

The Unfeathered Bird, she already had a background in fine art, museum curation (bird skin curation at the Natural History Museum) and book writing. I will fully confess to finding her skills and knowledge intimidating, and was a little frightened of meeting her at the 2015

TetZooCon. After all, if anyone was ever going to expose my work for the hack job it is, it would be this Baroness van Grouw, dual master of detailed anatomy and artistry (lightning flashes, thunder rumbles)*. It turns out that it's actually impossible to be scared of Katrina once you talk to her however, and we remain close friends today.

*Note that Katrina's status as a Baroness is a product of my over-active imagination, not reality.

There's lots to like about Katrina's books, and I mean no disrespect when saying that they're some of my favourite books simply to look at. Katrina's illustrations - drawn in pencil and then tinted to sepia tones digitally - are truly world class, and her subjects are frequently drawn in lively, life-appropriate poses so that, even when skeletonised or half-dissected, they look very much alive. But it's not only the drawings which make her books exceptional to behold: their size, ivory-coloured pages, font hues and text layouts recall a romanticised age of 19th century museums and scholarship. It's impossible not to think of exhibition halls filled with wooden cabinets, animal bones, taxidermy specimens, curiosities in jars and stuffy formalwear when reading these books. They evoke the atmosphere of a classic age of learning and exploration on every page. It must be stressed how, for their size and quality, both

The Unfeathered Bird and

Unnatural Selection are exceptionally good value for money ($45-50 cover price, but being sold at £20-25 at Amazon UK, and equivalent in the US). I can only wonder what Mephistophelian deal Princeton University Press has made to to sell these fantastic books at such low costs and, to the poor production editors suffering in the afterlife for making such a deal, know that it was really worth it: I can't think of many books published in recent years that are anywhere near as splendid to look at in this price bracket. For next-level book quality I can only think of tomes like the considerably more expensive (

but ultimately disappointing)

Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past (Lescaze 2017), with a cover price twice that of Katrina's books.

|

| Fans of The Unfeathered Bird will be intimately familiar with Katrina's skeletonised birds. Unnatural Selection offers a greater proportion of art devoted to living individuals, including this jungle fowl, the ancestral species of chickens. © Katrina van Grouw. |

But to only look at

The Unfeathered Bird or

Unnatural Selection would be a huge disservice to their scholarly content. The academic merits of

The Unfeathered Bird are widely known and I won't rehash them here - suffice to say that, if you're a regular reader of this blog, you'll want a copy. Although much newer, the amazingness of

Unnatural Selection has already been sung in several reviews and previews (

here,

here,

here,

here and

here) and I want to quickly add my own endorsement of Katrina's latest book before we delve into the interview.

Unnatural Selection is genuinely a fascinating and thought provoking insight into a side of evolutionary mechanics that we often ignore or stigmatise. Like many people - including other scientists - I've often thought that human-bred animals have little to tell us about evolution because they're somehow 'artificial', and that the genetic interplay that underlies their development somehow doesn't compare to what happens in 'real' natural selection. But Unnatural Selection shows the folly of this view, exploring how animal breeding reveals much about the ease and frequency of trait development, how our breeding choices are analogous to splitting and extintinguishing evolutionary lineages, the mechanisms behind expressing certain phenotypes, and evolutionary rates. Human-led breeding might be shaping animals towards a pre-ordained goal of our choosing, but it's still evolution. Ignoring it severs a wealth of insight and knowledge pertaining to evolutionary processes of any sort, human-led or otherwise.

|

| The strangely deformed skull of a King Charles spaniel. We view this sort of anatomical modification as extreme, and certainly there are welfare issues to consider with many domestic breeds (and not just dogs, as is most widely reported). But many of the extreme (and healthy) breeds we've created are no more bizarre than what we see in nature. In response to questions about pushing animal anatomy too far, Unnatural Selection responds "...look at what nature has done to the sword-billed hummingbird!". However we feel about the ethics of breeding bizarrely proportioned animals, we're not the only evolutionary force behind their creation. From Unnatural Selection, © Katrina van Grouw. |

It's worth stressing that this is not a book about the ethics of purebreds or pedigree lineages:

Unnatural Selection is book about evolutionary science viewed through the lens of domesticated species, and it leaves the politics and ethics of animal welfare at the door. Some may find the lack of ethical discussion a little peculiar given that any mention of animal fancy is so often presented hand-in-hand with animal welfare, but I can understand why this was left out: a good scientist presents their work objectively for society to implement as it sees fit, they don't present science to support their own opinions on a subject, no matter how strongly they personally feel about it. As an animal owner herself, Katrina is

on record as being just as concerned with the health of animal breeds as anyone, but she didn't feel her book was the place to share her opinions - I can respect this.

So yes, Unnatural Selection is a fascinating, unique and spectacular book that I heartily endorse. But that's enough preamble, over to its author and artist. I've included, with Katrina's help, a selection of artwork from The Unfeathered Bird, Unnatural Selection and some rarely-seen earlier works. All artwork in this post is Katrina's, and used with her permission.

--

MW. Much of Unnatural Selection discusses the prolonged challenge of having artificial selection viewed as having useful insights on 'natural' evolution. As you argue, this seems peculiar - a bit like a physicist arguing that experiments done on atomic particles in the lab have no bearing on 'naturally occurring' particles. Why do you think this issue has persisted for as long as it has?

KvG. I honestly have no idea. I too used to be what I call a ‘wild animal snob’ i.e. I considered domesticated animals as something man-made and irrelevant, though I’ve come to revise my opinions significantly!

It’s always said that Darwin drew up his analogy between natural and artificial selection specifically in order to introduce to the Victorian public the frightening concept that all the diversity of life could have come about without the need for a divine creator. Like the spoon full of sugar that makes the medicine go down. I suspect, as Darwin later maintained in his revised autobiography, that artificial selection was indeed highly influential in the formulation of his theory.

However, even Darwin had problems accepting that certain radical traits (like achondroplasia, or disproportionate dwarfism, discussed in the next question) could be successful in the evolution of wild animals, so he drew a line between them.

Richard Goldschmidt in the 1940s also made macro mutations appear ridiculous as a result of his ‘hopeful monster’ theory, which may have caused scientists to dismiss selective breeding as useless in comparison with evolution in nature. As you’ll be able to see from the next question, and especially in the book itself, there is actually very strong evidence that the same traits not only occur in wild animals, but may be favoured by natural selection.

|

| Four-winged dinosaurs have evolved a number of times, including at the hands of pigeon breeders (pigeon hindwing, or 'muff' foot, shown at the base of the image). Understanding the genetic changes behind the development of such traits may help us understand the mechanisms through which these evolved in nature, something of obvious interest to palaeontologists interested in development of stem birds and avian flight. From Unnatural Selection, © Katrina van Grouw. |

Every so often geneticists make a so-called breakthrough revealing some trend in domesticated animals that sheds light on evolutionary biology, and invariably these ‘discoveries’ have been known already to generations of animal fanciers who breed them. Feathered feet in pigeons are a good example. Every pigeon fancier knows that the wing-like ‘muff’ feet (palaeo-people will know these as ‘hind wings’) are produced by combining two very different foot feather types. Geneticists would do well to pay attention to the knowledge of animal fanciers instead of constantly re-inventing the wheel.

Whereas in past centuries scientists had eclectic interests and would happily turn to the products of horticulture as to botany, or to animal breeding as to wild animals, it seems that the more knowledge that’s available the more blinkered and over-specialised scientists become. I even know molecular geneticists who don’t fully understand Mendelian principles.

Sadly for too many of us, even though the subject of domestication is currently very popular in scientific circles, selective breeding is viewed either with derision or contempt. Fit only for children or eccentric losers, or an emotive subject to stir up the wrath of animal welfare crusaders.

I hope that my book will do something to redress the balance.

Unnatural Selection draws attention to the rapidity of evolutionary modification, specifically how animal form can be dramatically modified in a generation thanks to single genetic changes. You somewhat playfully speculate that this may have had a role in the evolution of some groups - such as the short limbs of mustelids: would you care to suggest - speculatively or otherwise - if any other groups may have benefited from these rapid changes?

That’s right. Though it’s important to stress that the most significant evolutionary change is the result of an accumulation of tiny steps – ‘natura non facit saltus’, as Darwin was fond of saying: ‘nature does not make leaps’. But there are plenty of traits that are single step, all or nothing, changes. Think of the spiralling direction of shells, or horns, for example. Colour aberrations too can result in major phenotypic changes just by the addition or subtraction of a pigment. (Colour ‘aberrations’ are only aberrant when they’re in low numbers in a population, but if they prove to be advantageous, or if they’re isolated in a small gene pool, these aberrations of today can be the colour morphs, races, or even species of tomorrow.)

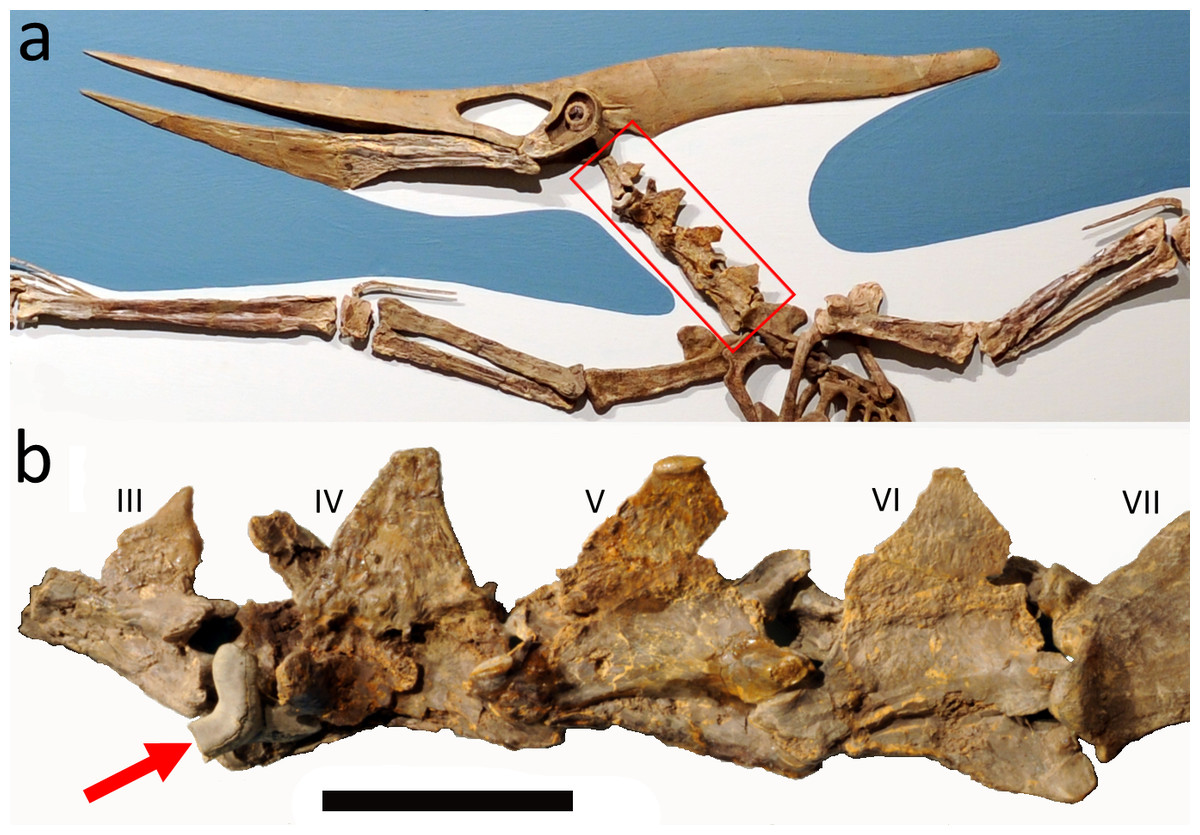

|

| Vertebral counts are considered a big deal in vertebrate palaeontology, often being used to distinguish different species. It turns out that gaining additional vertebrae is not particularly difficult and is not just the remit of weirdos with extreme numbers of axial elements, like snakes. We've emphasised this trait among species that we harvest for meat, such as landrace pigs, which have several more vertebrae than other breeds. From Unnatural Selection, © Katrina van Grouw. |

However, I’m deviating in my preamble. There are lots, and lots, of other examples, besides the short limbs of mustelids, where you can suggest, speculatively, that the evolution of wild animal groups may have been given a ‘leg up’ (no pun intended!) by a single major mutation. The naked neck trait in chickens is a good one - the heat-reducing naked necks of marabou storks, ostriches, and vultures is comparable and is probably caused by the same genetic process. Henny feathering in chickens (where the male has the same plumage as the female with no loss of virility) possibly has a connection with the seasonal eclipse plumage in waterfowl. Mutations that cause winglessness in chickens may sound pretty gross, but moas were totally wingless too, and there’s no fossil evidence to suggest that they ever went through a gradual evolution towards winglessness. Rex fur in rabbits may seem like just a fancy coat type for the show bench, but a similar coat (without directional guards hairs) allows moles to move freely backwards and forwards in their burrows.

The exact same mutations are equally likely to occur in wild as domesticated animals and their success is all down to whether or not they find themselves in an environment that’s favourable. The ‘right’ environment can come in many forms, and it can change, but traits that might not be successful in the wild for whatever reason might just appeal to the whims of fanciers. There are only a finite number of possible traits that will ever be viable, and the same things tend to occur across a wide range of animal groups, albeit expressed differently. Meaning that speculative zoologists would do well to pay more attention to domesticated animals and the traits they exhibit. This is variation in its most likely forms and a very accurate suggestion of the possible directions evolution might take in the future. Again, the initial mutation only needs to be a start. After that, natural selection can refine it further and fine tune it over millions of years to each particular environment.

Both The Unfeathered Bird and Unnatural Selection are simply stunning to look at, but not all your readers will know how instrumental you were to their design, not only creating the text and illustrations, but also having tight control over the page layouts and overall aesthetics. I gather this level of control is not typical in publishing, and it very much makes these your books. Can you tell us a little about your design decisions?

I’m glad you asked that; indeed, most people assume that the publisher designed the books, which is the more normal arrangement. I’m exceedingly lucky to have a publisher that has so much faith in me.

After nearly two decades of trying to find a publisher for

The Unfeathered Bird, I was painfully aware that many people associate anatomy with greyscale diagrams in academic textbooks. I wanted it to be as much a work of art as of science, so changing the colour of the finished pencil drawings to a sepia brown colour, and printing onto ivory-coloured paper was a deliberate attempt to make the book softer and more accessible and to be suggestive of the beautiful historical natural history illustrations of past centuries. This particularly suited the historical theme of both books:

The Unfeathered Bird references Linnaeus (this was a clever way to discuss adaptations through convergence rather than adhering to actual phylogenetic relationships) and

Unnatural Selection is all about Darwin and Mendel.

|

| The many faces of exhibition homing pigeons, an example of one of the full page spreads from Unnatural Selection. I can't be the only one thinking the Exhibition Homer resembles a certain piece of Therizinosaurus artwork. © Katrina van Grouw. |

Personally designing the books sort of happened by accident – I preferred to prepare the digital image files because I was reluctant to allow the original drawings out of my care. Also, I knew exactly how the different images on the page should be arranged in relation to one another. The drawings are all done on separate pieces of paper, so putting them together digitally myself seemed to make more sense than trying to explain where they should go. After that I discovered that my publishers were also happy to let me choose the fonts, guide the positioning of text, and even design the entire jacket, all of which I loved doing.

I had a lot of fun designing the page layouts, especially the chapter opening pages in

Unnatural Selection where I’ve shown historical museum specimens against antiquated-looking background paper. And the three coloured images in the book where I discuss pigment changes. The ‘let’s colour a Gouldian finch!’ page was based on Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe prints, with more than a passing nod towards Edward Lear’s coloured birds. This pleased me immensely as John Gould treated Edward Lear very badly in life, so it seemed like justice for Lear!

I'm curious about the poses of many of your subjects. Where you have control over this aspect of their illustration, what helped you decide to pose them a certain way, other than the simple practicalities of "I want to show this feature"?

Many of my decisions were indeed guided by ‘I want to show this feature’.

The Unfeathered Bird is all about adaptations, so it was important to show the features that I describe in the text as being particularly adapted to specific behaviour. So it made sense from a scientific and aesthetic point of view to show skeletons actually engaged in that behaviour. Husband put together the majority of the skeletons so it seemed fair to give him an input into the choice of positions. We had endless pleasure discussing the behaviour of birds and arguing (in a friendly way) about which position to choose.

Of course it’s not just the position of the actual skeleton, but the viewpoint I select to draw it from. The diver in the surface swimming position may be fairly straightforward, but I decided on a fish’s-eye view, looking up at it from below, as this was the viewpoint that most clearly showed the boat-like sternum, sideways-angled hind-limbs, and razor-thin legs.

|

| A budgie skeleton passes the mirror test, from The Unfeathered Bird. © Katrina van Grouw. |

Some of the poses, although superficially just for fun, are for practical as well as aesthetic reasons. The budgie skeleton looking at itself in a mirror in

The Unfeathered Bird was a way of showing both sides of the skull in the same drawing (while making it crystal clear that it’s a budgie!). I did the same thing with the reflection in the water under the porpoising penguin.

I enjoyed playing around with visual references, for example I deliberately showed the avocet in the same position as the RSPB logo; the red grouse was modelled on the whisky label, and the robin on the spade handle was modelled on 90% of the Christmas cards ever printed!

For all the major bird groups I included a page showing the feather tracts, musculature and skeleton of a species all together and for these it made sense to show them like an actual group of birds interacting. So I made up little tableaus: three rooks rushing to get a worm that’s just disappearing underground, or a pigeon’s frantic pouting courtship ritual being completely ignored by the other pigeons only intent on eating.

|

| The skeleton of the mighty auroch, one of my favourite pieces from Unnatural Selection. Katrina didn't pose this individual (it's based on a museum mount) but has really captured its implied energy and mass. We might be looking at a skeleton, but you can almost see the muscles rippling as the animal moves. From Unnatural Selection, © Katrina van Grouw. |

I can't look at your anatomical work without wondering how you could translate your skill into palaeoart, and I must not be the only person imagining that a van Grouw restoration of a fossil bird or (based on some of the amazing work in Unnatural Selection) a fossil mammal would be spectacular. Will we ever see a life restoration of a Gastornis, entelodont or Microraptor emerge from your pencils? And can I have a copy if it happens? I'll be your best friend.

|

| Proof, as if it were needed, that Katrina knows her way around skeletons and musculature as well as the best palaeoartists: a parade of cow bottoms. Note the 'double muscle' individual at the end of the row. From Unnatural Selection, © Katrina van Grouw. |

Haha, if it happens I promise you you’ll be the first to know! Probably because I’ll need your help to get it right and won’t be brave enough to show it to anyone until you’ve given it your seal of approval! I’m not adverse to the idea, but at the present moment I can’t envisage how it would fit into the planned book projects which, for the foreseeable future, will be purely anatomical.

It’s not entirely impossible though. With the right incentive (for example, producing commissioned illustrations for someone else’s book) I could probably be persuaded.

|

| Katrina's take on Pomarine skuas. I can't be the only person wanting to see this anatomical expertise and style applied to fossil animals. © Katrina van Grouw. |

Before your recent books you were best known for your work illustrating fantastic cliffs and seabird colonies. These are amazing images and I understand a number of folks were sad to hear you declare that this part of your artistic life is behind you. Is the door completely closed to this sort of wildlife art, or will it reinvent itself in some form? And if not, what lies ahead?

When I finished

The Unfeathered Bird I was fully intending to return to those sorts of pictures and to being a fine artist again, but I found that I’d moved on. It’s not that I refuse to do the same work; it’s because my heart is somewhere else now. You can’t force it – it has to come from genuine passion. Ever had a persistent ex who tries to convince you that you can fall in love with them again, while you know damned well it ain’t ever gonna happen? It’s a bit like that.

|

| One of Katrina's pre-Unfeathered Bird cliffscapes, St. Abbs Head, Scotland. © Katrina van Grouw. |

To be brutally honest I have nothing but contempt people who find it sad that I no longer do the same old work. It shows a lack of respect for my artistic integrity. It wouldn’t be so bad if these were faithful collectors and patrons from my past, but they’re not. Most, in fact, are creative people too so they should understand that creative development is a one-way process and not a matter of personal choice.

Before the rocks/seabird colony drawings I did images of big dramatic birds doing exciting things: fighting and chasing each other and stuff. Then I had a… I guess you’d call it an epiphany, on the cliffs of Hermaness in Shetland, and my work changed to the rocks overnight. And yep, you’ve guessed it, loads of people expressed regret that I wasn’t still doing the same bird pictures…

The important thing to remember is that the illustrations in my books are just that – illustrations. The book’s aren’t art books showcasing my anatomical art; they’re science books – albeit very beautiful ones. Each illustration is just a means to an end and a very small part of the whole. To me the creation of the book – the entire book, from conception to design - is the creative process. What can possibly be finer than bringing into existence an entirely original and very beautiful book?! It ticks all the boxes for me at every creative and intellectual level.

The important thing is to bring all this stuff – pictures or books or whatever - into the world, and the fact that it can’t be relied upon to be repeated forever is what makes it precious. I don’t know what lies ahead, of course, but I think it highly unlikely that I’ll ever return to being a fine artist. But if I do develop in an unexpected direction, promise me you won’t say it’s sad that I no longer produce books!

|

| Katrina's terrifically moody albatross piece, a big dramatic bird doing an exciting thing. A skeletonised version of this image graces the opening of The Unfeathered Bird. © Katrina van Grouw. |

In some respects we have arrived at a similar career path from opposing directions: I became an author/illustrator through training as a scientist, while you trained as an artist before authoring science books. You mention in Unnatural Selection that this professional path was not without its struggles, and I can entirely empathise with this. You have to become equally skilled in two, sometimes very different fields and practical issues mean it's not easy to be highly trained in both. Despite these challenges, you've produced two spectacular and very well received books. How have you dealt with the challenge of transitioning from artist to author who does art?

To be fair to myself, although I was deprived of the opportunity of a formal science education, my world before

The Unfeathered Bird wasn’t entirely devoid of science, though it was practical rather than theoretical. I was a passionate birder from childhood, and my interests led me to train as a bird ringer in my early 20’s. I took part in long term ringing expeditions to Senegal and Ecuador and was particularly interested in moult and other physiological indicators that ringers use to age and sex birds. Around this time I taught myself taxidermy and began to assemble my own bird skin collection, and also prepared bird skins for museums. The personal project that let to me to make an in-depth study of bird anatomy (beginning with a dead duck I christened Amy) has been told many times already. Ironically, many of these elements are not things that science undergraduates are taught. I know plenty of lettered biologists who have never even touched a scalpel. That was all back in the late 1980’s so the transition into science hasn’t been a sudden recent change.

Anyone can educate themselves. The difficulties lie in the lack of opportunity for discussion with peers and tutors, and the difficulty of accessing academic texts, but it’s certainly not impossible. Harder to throw off is the bias based on your actual qualifications.

|

| A disproportionately dwarfed "ancon" sheep, an example of a single-step evolution. Such sheep are more common than we may expect, and we have to wonder how often such radical changes occur naturally. It's conceivable that major, single-step changes in animal form could be selected for under some natural circumstances, and may have even played a role in 'natural' animal evolution. From Unnatural Selection, © Katrina van Grouw. |

What I find most difficult, and personally infuriating, is people’s preconceptions; the tendency to put two and two together to make five. Many people find it difficult to accept that someone with an art background can have a genuinely scientific interest in something. They’ll assume that my anatomical interests have an artistic root – as though I’m inspired by textures and shapes and all that. And of course I do enjoy drawing this sort of thing, but it’s not the reason for it. I try to explain that if I wasn’t producing books, I wouldn’t be drawing skeletons, but no-one wants to hear that. Even on my book tour this year I sometimes had to really fight to be described as an author and not an artist. One venue insisted on advertising my talk: ‘Katrina van Grouw’s evolutionary illustrations’. It was humiliating.

The most damaging element of all this, and one that I find deeply painful, is the assumption that I must rely on Husband to help me with the science in my books, because I’m an artist (‘only’ an artist is the unspoken word here). In fact neither of us have an academic science background, and both of us formerly shared a career as curator of the bird collections at the Natural History Museum. Husband is indeed useful for mounting skeletons, and for his knowledge of domesticated animals, but I’m the one with the interest in evolutionary biology.

All in all it seems to be a lot easier for a scientist to be respected as a self-taught artist than the other way around.

Being self-taught does have its plus side however. Having to learn science the hard way means that I know a lot of the pitfalls and barriers to grasping each subject, so I’m in a good place to explain difficult concepts to others in a clear way. It’s made me a really good science communicator.

Given that this is primarily a palaeontology-led blog, I feel we should end with the news that The Unfeathered Bird will be making a return at some point in future, and will have a significant palaeo-themed component this time. Can you give any hints as to what to expect?

Yep, that’s right. I actually signed the contract to do a second edition of

The Unfeathered Bird last spring, but I haven’t quite gotten into gear with it yet due to all the work of production and publicity for

Unnatural Selection.

It’ll have an extra 96 pages, making a total of 400. You’ll remember that the first edition is divided into two sections: ‘generic’ – talking about birds in general - and ‘specific’ – talking about particular bird groups. The new material will mostly go into the generic section, looking at the definition of what makes a bird, what birds are and aren’t, and of course a whole load of stuff about bird evolution.

|

| Red throated diver skeleton, from The Unfeathered Bird. A new edition will be with us one day! © Katrina van Grouw. |

Bird wings will be compared with bats and pterosaurs (and

Yi qi?). There’ll be stuff about feather evolution (maybe I can get a palaeo reconstruction in here somewhere...), lots of stuff about the loss of digits, the rotation of the wrist, shortening of tails, lengthening of necks, and the orientation of thighs. And you can expect a few active maniraptoran skeletons doing maniraptoran things.

In addition to this I’ll be replacing some of the drawings in the ‘specific section’; adding some more and giving the existing ones a good polish. I’ll be completely re-writing all the text and replacing the short family sections with entire chapters. The total word count is estimated to be around 110,000 words, in comparison with the 46,000 of the first edition. The science will be better, though still easily accessible. There’ll probably be a new jacket design, but almost certainly still showing peacocks. And I’m guessing the original title will be followed by a subtitle (suggestions on a postcard, please).

The Unfeathered Bird NEEDS a palaeo-themed component. It’s incomplete without it, and any reviewer who wanted blood could easily and justifiably have torn the first edition into shreds. But that didn’t happen. Instead the palaeo-world received us with open arms and heaped praise upon us. It was possibly the most humbling experience of my life. This new edition is my way of expressing my gratitude.

--

Thanks very much to Katrina for the interview, and please leave your suggestions for the subtitle of the next edition of

The Unfeathered Bird in the comment field below. Personally, I'm thinking

Unfeathered Bird II: The Birdening;

UB2: Judgement Day; Unfeathered Bird: First Blood Part 2; or

The Return of the Unfeathered Bird: Rave to the Grave. Alternatively, use those same seconds to grab yourself a copy of

Unnatural Selection and

The Unfeathered Bird, both available now from Princeton University Press and all good bookstores.

Enjoy monthly insights into palaeoart, fossil animal biology and occasional reviews of palaeo media? Support this blog for $1 a month and get free stuff!

This blog is sponsored through

Patreon, the site where you can help online content creators make a living. If you enjoy my content, please consider donating $1 a month to help fund my work. $1 might seem a meaningless amount, but if every reader pitched that amount I could work on these articles and their artwork full time. In return, you'll get access to my exclusive

Patreon content: regular updates on research papers, books and paintings, including numerous advance previews of two palaeoart-heavy books (one of which is the first ever comprehensive guide to palaeoart processes). Plus, you get free stuff - prints, high quality images for printing, books, competitions - as my way of thanking you for your support. As always, huge thanks to everyone who already sponsors my work!