|

| It's Christmas time, which means it's time for a festive book review! This year's subject: John Conway's A History of Painting (with Dinosaurs). |

It was ten years ago that palaeoartist John Conway, along with his colleagues Memo Koseman and Darren Naish, published one of the seminal works on palaeoart for the modern age: All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals (Conway et al. 2012). Seeing that palaeoartists of the 2000s and early 2010s were already chipping away at the “rigorous reconstruction” conventions established by palaeoartists of the late 20th century, All Yesterdays blew them apart entirely by drawing focus to the “known unknowns'' of restoring fossil organisms. It not only pushed for greater experimentation with style and subject matter, but also, in its cleverest trick, revealed the hilarious/horrific results of applying palaeoartistic techniques to living animals. The slew of online discussions, artworks, memes and projects that followed All Yesterdays have been of variable quality and legitimacy, a comment that applies to the lesser-mentioned crowdsourced follow-up, All Your Yesterdays as anything else, so the legacy of this book is a complex one and there are discussions to be had about its long-term impact. But however we feel about All Yesterdays, we can’t deny that it has shaped much of the conversation around palaeoart in recent years. Its name has, deservedly, become synonymous with the current, postmodern era of extinct animal reconstruction (Witton 2018; Nieuwland 2020; Manucci and Romano 2022).

A decade later, John Conway is back with another book — and this time it’s personal, or, at least, a solo-authored book project, aside from a foreword written by English Literature scholar and dinosaurophile Will Tattersdill. This volume, A History of Painting (with Dinosaurs), imagines what art history may have been like had the great masters of Western art chosen prehistoric animals as their subjects of choice rather than people, landscapes or constructs of human society. It’s hard not to see this, at least partly, as a deep-dive into one of All Yesterdays’ threads about deviating from traditional palaeoart styles. The sense that A History of Painting is a spiritual successor to All Yesterdays also ebbs from its identical size and length, its print-on-demand publishing model, as well as its low price (£19) and sometimes playful, winking tone. But the similarities end there: whereas All Yesterdays used a scattergun approach to critiquing palaeoart in 2012, A History of Painting is a book with a singular point to make.

What that point is, though, is for readers to decide. In John’s own words, “A History of Painting is either a big joke that will make you smile, or a serious questioning of subject matter in art that will make you think”. If A History of Painting is, indeed, a joke, it’s had a long build-up to its punchline. John has been working on this book for two years and produced 50 new paintings specifically for this project, only a few of which can be found online (I've used nearly all of them in this post). They are some of John’s most interesting pieces yet — which is no mean feat, given the quality of his artwork in general — and cement his reputation as one of the most important palaeoartists working today. He has created a series of pastiches of artwork from the 14th to 20th century that range from caricatures of iconic artworks (Mona Heterdontosaurus or The [troodontid] Scream, anyone?) to more “serious” efforts at injecting palaeoart into famous paintings or artistic styles. While a certain amount of Conway DNA exists across each painting, the diversity of styles and genres is seriously impressive and I could easily believe several artists contributed to this book. It’s difficult to think of another palaeoart volume that varies so much stylistically, and I’m including multi-artist compendiums like Mesozoic Art in that consideration. If you’re a fan of Conway palaeoart, you need to grab this for its art alone. I can give no better indication of the quality of artwork than mentioning that I bought a large print of one of the paintings at the launch event (below), and it’s going to be framed and hung in the house somewhere.

|

| Proof, if proof be need be, of my ownership of these Conway Moospods. The animals here are Saltasaurus, rendered over Ploughing in the Nivernais by the 19th century animalier Rosa Bonheur. Art by John Conway, from Conway (2022). |

Had A History of Painting only been filled with dinosaur-flavoured riffs on da Vinci, van Gogh or Warhol, I’m not sure I’d be writing about it here. John’s takes on these iconic works are great but we’ve seen so many imitations and parodies of the paintings in question that there’s not much more to be mined from reimagining them, even with dinosaurs. Happily, A History of Painting is mostly comprised of unexpected mashups of paintings and palaeo: a sauropod-themed reimagining of Bacon’s biomorphic Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, a Late Gothic battle scene retooled with lances swapped out for sauropod necks, a bellowing theropod set against the same lightning flash that frightened Delacroix’s horse. It’s among these that any pretence of the book is a joke falls away, because anything but the most superficial glances at such works gives cause to reflect on dinosaur art more generally. Seeing dinosaurs in such artistic contexts is simply incorrect, but the quality of their superimposition is such that they can’t be dismissed as crude puns at the expense of historic masters. Rather, this juxtaposition of dinosaurs in “serious” artworks gives much to think about palaeoart, our wider attitude to dinosaurs, and maybe even our relationship with nature itself.

Because the book itself is light on text, I found knowing something about the origins of A History of Painting helped my reading of it. Back in 2017, John gave a public talk at a Popularising Palaeontology event about the interaction between dinosaurs and mainstream art, or lack thereof. In a whirlwind tour of the history of painting, John argued that innovations in style have been pursued at the expense of innovations in subject matter, tracking how Western art initially fought to capture the basics of reality, eventually achieving what we’d today describe as hyperrealism or photorealism, and then pushed back to explore new movements like expressionism, surrealism, and abstraction, cumulating in works such as Rauschenberg’s 1951 White Painting. Style, John argued, is now a dead-end for experimentation, with artists having reached beyond reality into the furthest reaches of the abstract. But in terms of subject matter, mainstream artists have remained pretty focused on matters of humanity: our own form and appearance, our religions, beliefs and cultures, our dramas and tragedies, and the local world we inhabit. So if style is dead, maybe the next artistic frontier is… subject matter? And if artists want to continue pushing boundaries and the limits of human experience, what would make better subjects than extinct animals?

|

| The unmistakable painting approach of Gustav Klimt, reworked to feature hadrosaurs. It's recognisably palaeoartistic, but not as we know it. Art by John Conway, from Conway (2022). |

It’s this line of thinking that gave rise to A History of Painting. The opening of the book asks, bluntly “did the vast majority of artists really ignore the greatest subject of all, dinosaurs and closely related animals?”. Though approached somewhat facetiously, it's hard not to find some validity here. Consider the wealth of discovery we’ve experienced over the last few centuries: the reality of Deep Time and extinction, the endless parade of exotic organisms, living and fossilised, that exist and have existed on our planet, the vastness of the cosmos and the nature of other worlds, the fundamental components of physical reality… we could go on and on. And yet, these subjects, which represent the very limits of human knowledge and challenge our comprehension of reality and possibility, remain largely untouched by our most famous artists. Those of us that explore the details of the natural world aren’t part of the classic painter canon: we are given different labels (“scientific illustrators”, “wildlife artists”, “palaeoartists” etc.) and our work, if exhibited at all, is more likely to be shown in a natural history museum than the National Gallery.

John is, of course, not the first person to point out the divide between conventional art and palaeoart, nor to imply that palaeoart is undervalued (Mitchell 1998; Lescaze 2017; Manucci and Romano 2020). W. J. T. Mitchell (1998) and Zoe Lescaze (2017) have suggested several reasons for the obscurity of palaeoart, mostly pertaining to stylistic issues and facts of history. Mitchell regarded the work of prominent 20th-century artists as stylistic “throwbacks” compared to trends in mainstream art, while Lescaze argues that the genre draws on too many artistic influences — Romanticism, Impressionism Fauvism and so on — and thus presents a “cacophony of dialects” to scholars attuned to more unified artistic voices and styles. Mitchell further notes that palaeoart developed too late as a genre to capitalise on the animal painting craze of the 19th century.

But there’s a deeper issue, simply identified as “snobbery” by Lescaze (2017). The symbology of dinosaurs is all wrong for refined, dignified artistic traditions. In popular culture, dinosaurs are synonymous with spectacle, violence, mass consumption and childhood interests (Mitchell 1998; Lescaze 2017). Thusly, as Lescze (2017) observes:

“Throw an engraving of an egret above the mantelpiece and no one balks. Hang a painting of a T. rex in the same spot, and the decision screams nerd stuck in second childhood.”

Lescaze (2017), p. 268.

We might thus have some answers to John’s question, the most important being that great artists did not regard dinosaurs as we — as in, the scientists, scholars and enthusiasts who read blogs like this — do today. We think of prehistoric animals as amazing extensions of the living world, species that must have been as majestic and amazing and inspiring as the greatest of today’s creatures. But to non-specialists, these animals are vulgar, monstrous forms represented by tacky merchandise and blockbuster movies. Even if they followed the scientific thinking of the time, artists of the 19th and early 20th centuries would have regarded dinosaurs as inferior animals to mammals and birds (a view that might explain the absence of “lower animals” — invertebrates, reptiles and amphibians — in mainstream painting as well). And, of course, we have the longstanding, entirely false idea that art and science are inherently incompatible. These conspire, Mitchell concludes, to force dinosaurs into a niche well separated from the traditions of studio art:

“...the dinosaur seems to have its ‘proper’ place as the figurehead image of the natural history museum, [where] it helps to reinforce the illusion of a strict separation between nature and culture, science and art. The truth is, this separation is one of cultural status and has absolutely nothing to do with nature, which is just as much the object of art as of science.”

Mitchell (1998), p. 62.

By injecting dinosaurs into classic paintings, A History of Painting continues this discussion in a radical new way, allowing us to explore the inherent “wrongness” of seeing dinosaurs approached as “serious” art subjects. I see John’s book as a direct challenge to the idea that palaeoart must have a purpose, sensu Mitchell’s (1998) comment that “A cubist dinosaur would not be of much use, either to a palaeontologist or to the public” (p. 60). Three cubist paintings (Therizinosaurus, Triceratops and Ankylosaurus) allow us to judge that for ourselves. Are these “useful” paintings of dinosaurs? OK, they distort the appearance of the animals in question, but does a distorted dinosaur serve no purpose? Does bringing a cubist approach to dinosaurs deny us the interpretations we might discuss around conventional cubism, such as its capturing of movement or time, its use of multiple perspectives to convey three-dimensional shapes, and the use of a flat image to capture reality? And, more broadly, it asks why must art of dinosaurs be useful? Can it not be art for the sake of being art, or created purely for aesthetic value? As John pointed out at the A History of Painting launch, the unusual shapes and anatomy of dinosaurs allow for terrific abstractions if we can allow ourselves to abandon the idea that they should only be rendered in ways that show their bodies precisely and clearly. And, ironically, this very discussion already shows that John’s cubist dinosaurs have a purpose, inviting us to question our relationship with dinosaurs in art.

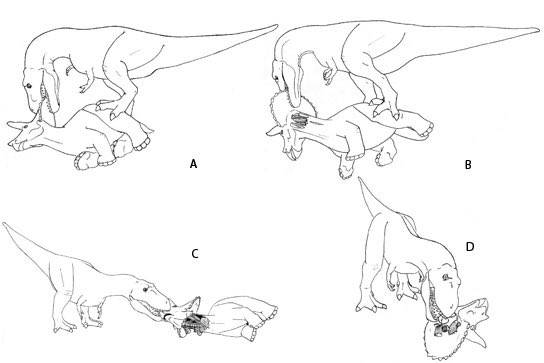

But lest it be thought that A History of Painting is full of strange and bizarre paintings, some works also allow us to recognise the roots of palaeoart itself. John demonstrates that conventional palaeoart has a home, at least stylistically, among the Romantic landscapes of Constable, Corot and Boheur. Here, John creates pieces where dinosaurs are dwarfed by richly painted, detailed surroundings, recalling Henderson-esque landscapes with a Romantic twist. Each could be dropped into a dinosaur textbook without raising eyebrows. His artworks allow for other reflections on palaeoart practises too. His German Renaissance-inspired take on Nemegt Formation dinosaurs allows for a surprisingly effective take on a classic“menagerie” scene with multiple species, the distorted perspective allowing animals of all sizes and shapes to remain visible and uncrowded in what would be an otherwise overly-busy scene. The intentionally warped anatomy of certain restorations provides a new perspective on animal monsterisation: the aforementioned Delacroix Therizinosaurus is disturbing and nightmarish, the reddish hues that accompanied the original facial features of the horse being extended across the face and neck in a fashion that recalls an open wound. And the large number of intimate portraits, often of theropods with forward-facing eyes, encourages us to consider dinosaurs as individuals, a goal we often pursue by adorning them with wear and tear (e.g. scars, scratches, blotches etc.), not quiet, close interaction with viewers. Needless to say, the great stylistic experimentation gives much to ponder about traditional approaches to rendering fossil species. Do some of the paintings in the book transcend “palaeoart” as we might typically define it, or are they "art that features dinosaurs"? Where would we draw the line? Should we even bother with lines at all?

|

| Tarbosaurus hunts Saurolophus in Cretaceous Mongolia, imagined here in Lucas Cranach's 16th Century style. Against all expectations, the strange perspective and lofty point of view make this potentially overcrowded scene very pleasant to look at: it's essentially 5-6 small paintings in one. Art by John Conway, from Conway (2022). |

We could go on: there is much to ponder over when thumbing through A History of Painting, and writing this has only prompted even more to think on and discuss. And it’s here, with my brain full of thoughts and ideas, that I find my only real concern (as opposed to criticism) about this project. Much of the above paraphrases points that John has raised in talks about his book, but there’s no substantial discussion of this nature in the book itself. Instead, it leads with a short meta-fiction, suggesting the paintings are recreations of a lost collection of dinosaur artworks by well-renowned artists. The descriptions of the paintings toe this line, making suggestions as to the original artists and subject matter as one might if recreating a series of images from photographs. It’s a fine enough set-up but I worry that it denies the book a context and, dare I say it, an importance that it might otherwise have had, risking it being seen as little more than an exercise in kitsch rather than a considered entry to an ongoing scholarly discussion. A version of A History of Painting was drafted that contained more explanation and text, but didn’t make the cut for being overly stuffy and academic: this is a book designed to appeal beyond a few historians and researchers, after all. I can’t criticise the book for the approach it’s taken because there’s surely no right or wrong way to frame such an unusual project, but I hope its approach doesn’t see it become ignored or brushed off as lightweight frippery. I feel John’s thoughts on this should be recorded somehow, and I wonder if those unused drafts would warrant being turned into a complementary paper or article. And, again, this idea gets my brain turning over: I’m curious to know what non-palaeontological artists and art historians would make of all this. Some sort of public discussion outside of the bubble of palaeo-enthusiasts could be a terrific event. But — no, we must stop.

This wanting the book to be discussed and contemplated is, of course, a strong, if indirect, recommendation for getting yourself a copy. Although it's probably too abstract to have the impact of All Yesterdays, A History of Painting (with Dinosaurs) is a book like no other and another important contribution to the palaeoart book canon from John Conway. Beyond being great to look at, it’s a thought-provoking exploration of not only the value and role of palaeoart, but of our societal relationship with extinct animals and nature, and all for just £19. At the time of writing, there’s still time to get it before Christmas and it should be available pretty much wherever Amazon operates (John has some quick links at his website, but check your national Amazon webpage for details). If you have any stockings to fill for a palaeoart fan, or perhaps for anyone interested in art history, this is well worth your money.

And having mentioned festive season, it’s time at the bar for 2022 at this (now ten-year-old!) blog. However you mark the end of the year, I hope you all have a safe and happy time, and I’ll see you in 2023.

Enjoyed this post? Support this blog for $1 a month and get free stuff!

This blog is sponsored through Patreon, the site where you can help artists and authors make a living. If you enjoy my content, please consider donating as little as $1 a month to help fund my work and, in return, you'll get access to my exclusive Patreon content: regular updates on upcoming books, papers, paintings and exhibitions. Plus, you get free stuff - prints, high-quality images for printing, books, competitions - as my way of thanking you for your support. As always, huge thanks to everyone who already sponsors my work!

References

- Conway, J. (2022). A history of painting (with dinosaurs). Independently published.

- Conway, J., Kosemen, C. M., & Naish, D. (2013). All yesterdays: unique and speculative views of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. Irregular books.

- Lescaze, Z. (2017). Paleoart: Visions of the prehistoric past. Taschen.

- Manucci, F., & Romano, M. (2022). Reviewing the iconography and the central role of ‘paleoart’: four centuries of geo-palaeontological art. Historical Biology, 1-48.

- Mitchell, W. T. (1998). The last dinosaur book: the life and times of a cultural icon. University of Chicago Press.

- Nieuwland, I. (2020). Paleoart comes into its own. Science, 369(6500), 148-149.

- Witton, M. P. (2018). The Palaeoartist's Handbook: Recreating prehistoric animals in art. The Crowood Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)