|

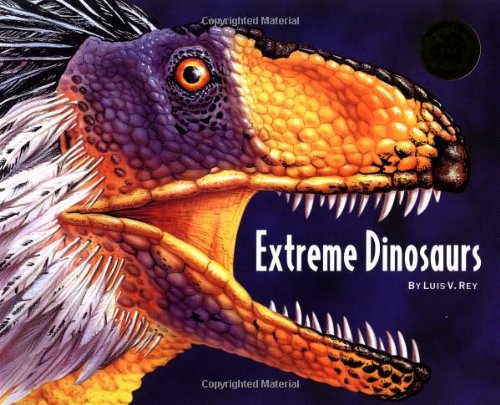

| Cover art for Luis Rey's 2019 book Extreme Dinosaurs Part 2: The Projects, featuring the latest incarnation of Luis' Deinonychus. Notice the presence of lips. Image borrowed from the Luis V. Rey Updates Blog. |

Unbelievably, the sun is already setting on 2019 and the holiday season is fast approaching. In keeping with the season, over the next two posts, I want to draw attention to two palaeoart-heavy products that I think are worthy of a place under your Christmas tree.

First up is a book by renowned Spanish-Mexican palaeoartist Luis V. Rey: Extreme Dinosaurs Part 2: The Projects. I bought Luis’ book earlier this year at TetZooCon and felt it worthy of writing up, not the least because, as a self-published volume, any and all advertising and promotion is helpful. Extreme Dinosaurs 2 is available in both hardback and paperback editions (my review is based on the paperback) from Amazon and eBay for £25 and £20, respectively, which I think is a very fair price for these well-produced, high-quality books. These are not print-on-demand self-published books that roll the dice with aspects like printing and trimming: they’re pre-printed and Luis-approved products that you’re buying directly from the Rey household.

|

| Cover of the first Extreme Dinosaurs, borrowed from Amazon.com, featuring the earliest version of Luis' Deinonychus. Such extensive feathering was pretty radical for Deinonychus in 2000, and there's an even more 'extreme' version inside. |

Extreme Dinosaurs 2 is billed as a sequel to Luis’ 2000 book Extreme Dinosaurs, though they are quite different in format and organisation. Extreme Dinosaurs is a fairly conventional popular dinosaur book at heart, overviewing dinosaurs from around the world in several themed sections. Fulfilling the promise of ‘extreme’ dinosaurs is Luis’ compositionally and anatomically radical dinosaur art which, in a palaeoart era dominated by Sibbicks, Pauls and Halletts, was unlike anything seen before. Luis’ enthusiasm for the then newly discovered Chinese feathered dinosaur fossils gave his work an additional revolutionary edge. Today, Extreme Dinosaurs is available only through second-hand markets but it is worth tracking down for the classic Luis Rey art it contains, as well as to own a time capsule from a major transitional period in dinosaur palaeoart.

Extreme Dinosaurs 2, in contrast, has a slightly narrower focus. It documents four major palaeoart projects and exhibitions executed by Luis in the last decade and feels like a more specialised volume as a result. While the opening section of the book, devoted to the evolution of feathers and skin, serves as a general overview of dinosaur palaeobiology and appearance (featuring art from Luis’ Dinosaur rEvolution exhibition), the rest of the book is more eclectic, with sections on Archaeopteryx and maniraptorans (from the exhibition: Feathers Fly; The Art of Archaeopteryx), dinosaur parenting behaviour (Hatching The Past), and Mexican dinosaurs (Dinosaurios Hechos En Mexico). It holds together as a book and contains many 'firsts' as goes restorations of newly discovered Mexican taxa but, as a collection of personal projects, it doesn’t work as well as the first as an introduction to contemporary dinosaur palaeontology. This isn't a problem of course, but it's worth noting - if thinking about this as a gift, say - that readers who aren't already fairly nerdy about dinosaur palaeontology might struggle with some of the content. As with Extreme Dinosaurs, I suspect its main appeal will be the vast quantity of Rey artworks it contains. At over 130 pages it’s more than twice the size of its forebear, and the number of illustrations is extraordinarily high. It really is a bonanza of Reyian dinosaurs, where animals lurch at you or at each other with every page turn. Luis’ artistic flourishes make this a tour through the Mesozoic like no other - a Reyozoic, if you will - and if you’re a Luis fan, it’s a must-have for this reason alone.

|

| A lot of Rey artwork features predation, but it's not all animals leaping from the page towards your face. Here, the giant Mexican hadrosaur Magnapaulia is pursued by albertosaurines. I particularly like the purple and yellow hues in this scene, and the size of the Magnapaulia is conveyed well. The inclusion of many obscure, rarely illustrated Mexican species is definitely a plus point for Extreme Dinosaurs 2. Image from Luis' blog, © Luis V. Rey. |

|

| One of the aspects I admire most about Luis' artwork is his consideration of integument. Although guided by phylogenetic bracketing, he plays with skin variation within clades and across individual animals, creating unique - but not implausible - takes on species such as Deinonychus and Nothronychus. From Luis' blog, © Luis V. Rey. |

|

| Luis remains entirely unafraid of creating extreme takes on fossil animal behaviour and form, and that takes... whatever this Allosaurus used to have where those spikes are now. This image is based on a real Allosaurus specimen with a pathological pubic boot, as outlined at Luis' blog. Image © Luis V. Rey. |

While it’s difficult for Extreme Dinosaurs 2 to recreate the anatomical wow factor of the original book, the boldness of Luis’ work remains as strong as ever. Luis’ palaeoart has a reputation for polarising opinion but, whether you’re a fan or not, it’s hard to argue that his art is not thought-provoking, ambitious, and an important reminder to never get too comfortable with convention. Indeed, there’s a fearless quality to Luis’ work. It confidently challenges expectation about what ancient animals looked like, while never advertently straying from the confines of fossil data. Look beyond the saturated colours and elaborately fuzzy animals and you'll notice that Luis is often highly attentive to details of specimens and palaeoecological scenarios, creating whole scenes around pathological specimens and overhauling older works to bring them up to date with modern science. Several such examples are seen in Extreme Dinosaurs 2, such as new art showing Triceratops being decapitated by Tyrannosaurus (as suggested by fossil data) and older paintings being updated to better match current interpretations of feather distribution or soft-tissue arrangements. The addition of lips to most of the dinosaurs in Extreme Dinosaurs 2 feels like a major departure from older Luis works, the lipless jaws of his foreshortened animals being, in retrospect, an obvious characteristic of many of his paintings.

I like the fact that Luis works within, but is not a slave to, phylogenetic bracketing, and his work implies that the appearance of fossil species may have varied significantly within clades. His large dromaeosaurs, for example, aren’t just larger versions of the ‘ground eagles’ indicated by small-bodied fossil specimens, but instead have ostrich-like naked legs and shaggy, messy feathers which could reflect flightless habits. He is unafraid of applying large tufts, long fibres and fleshy skin to his restorations in ways which can seem odd, but only because Bornean bearded pigs, porcupines and turkeys are not our go-to reference taxa for most dinosaurs. Luis’ lack of concern for making animals look peculiar or downright daft is a rare asset, and one of the things I admire most about his palaeoart.

I like the fact that Luis works within, but is not a slave to, phylogenetic bracketing, and his work implies that the appearance of fossil species may have varied significantly within clades. His large dromaeosaurs, for example, aren’t just larger versions of the ‘ground eagles’ indicated by small-bodied fossil specimens, but instead have ostrich-like naked legs and shaggy, messy feathers which could reflect flightless habits. He is unafraid of applying large tufts, long fibres and fleshy skin to his restorations in ways which can seem odd, but only because Bornean bearded pigs, porcupines and turkeys are not our go-to reference taxa for most dinosaurs. Luis’ lack of concern for making animals look peculiar or downright daft is a rare asset, and one of the things I admire most about his palaeoart.

|

| Many aspects of Luis' work - from his posing to his muscular, athletic animals - remind me of Bob Bakker's palaeoart - it's unsurprising that Rey-Bakker collaborations have been plentiful over the years. Here, Tarbosaurus runs down Gallimimus. Image from Luis' blog, © Luis V. Rey. |

Extreme Dinosaurs 2 showcases Luis’ work from the last decade or so, which means it more or less exclusively features digital photo composites over traditional paintings. Many of the featured artworks are murals, and we are treated to glimpses of early sketches showing how these came together. Luis’ use of photo composition has not been universally welcomed, with some preferring his older work executed in traditional media. This might be a deciding factor for some potential customers of this book but… read on a little further before you make up your mind. I’m going to be honest and confess that I’ve not always been a fan of Luis’ digital works, but that Extreme Dinosaurs 2 has given me cause to change that view. For one, the images simply look better in this well-produced book than they do as low-res online versions, being both appreciably sharper and more detailed. I don't think they're always successful but, hey, show me anyone who can flawlessly execute 130 pages of photo-real images. In many cases, the lighting and texturing of the animals is genuinely very good, giving a great sense of three dimensions to a medium which often looks flat.

|

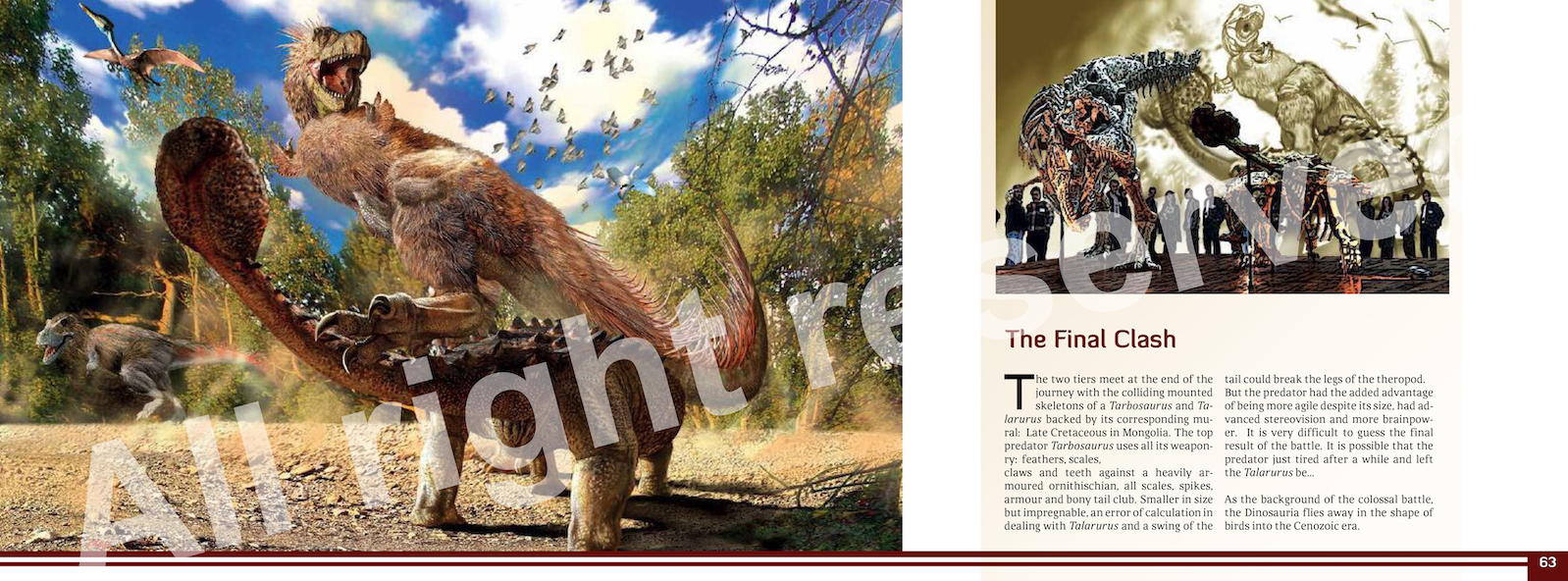

| Double page spread from Extreme Dinosaurs Part 2, showing a mural with battling Tarbosaurus and Talarurus. The arrangement of this photo composite is classic Luis Rey, despite the challenges of this medium. Image borrowed from Luis' blog, © Luis V. Rey. |

Third, after immersing myself in page after page of modern Reyian colours and composition, I started to suspect that Luis is not, as is mostly the case with photo-composited palaeoart, going for strict photo-realism. Luis has, after all, a background in surrealist and abstract art, and you can see the influence of these genres even in his traditional work. There is something pseudo-surreal and semi-abstract about some of Luis’ busy, highly active scenes of arching bodies, extremes of body size and perspective, and colliding colours and texture. Combining landscape photographs, original paintings, bits of toys and models, cropped and recoloured animal skin, cloned elements and texturing effects into classic Reyian scenarios is a terrifically bonkers way to reconstruct extinct creatures, and seems almost reflective of how we mentally conceptualise these animals from different references: a little of this living animal, some of that painting, a pose from that museum mount... and so on. This collaging effect sometimes avoids looking real, but Luis' images never fail to look alive. I have a lot of respect for Luis for pushing photo composition in his own way and think some of the results are genuinely striking. The images can still read as straight reconstructions of extinct subjects (and I think this is how most people are appreciating and judging them), but there’s an artistic quality to them which we should also admire, especially as the palaeoart community calls for more interesting styles and experimentation among its practitioners.

|

| Scenes such as this Therizinosaurus rookery/life cycle image are so packed with action, colours, textures and characters that, for me, they transcend conventional natural history art and dip their toes into a surreal, larger than life version of prehistory. Luis has made a name for himself creating scenes like these, and his distinctive style is, I think, a terrific addition to the more conventional palaeoart that folks like myself produce. Image from Luis' blog, © Luis V. Rey. |

But... whatever. Extreme Dinosaurs Part 2: The Projects is an enjoyable book and a firm reminder of Luis' importance to palaeoart. It works as a fun and interesting read or simply as a vessel to own Luis' most recent illustrations, and the production quality and amount of content represent excellent value for money. In being almost 140 pages of entirely unfiltered, undistilled Reyian palaeoart this is definitely a book for Luis fans and palaeoart collectors, although there's no compromising here to convert anyone with a strong dislike of Luis' style. But, as one of palaeoart's most iconoclastic practitioners, I'm pretty sure Luis wouldn't have it any other way.

(One final word on Extreme Dinosaurs 2: if you've already got a copy, and have enjoyed it, please help Luis out by spreading the word on social media or leaving a review at the web store you used to buy it. I know from experience that word of mouth is critical to the success of self-published books and, if we want to see Extreme Dinosaurs Part 3: This Time It's Extremely Personal, we need to help this book reach its audience.)

Enjoy monthly insights into palaeoart, fossil animal biology and occasional reviews of palaeo media? Support this blog for $1 a month and get free stuff!

This blog is sponsored through Patreon, the site where you can help online content creators make a living. If you enjoy my content, please consider donating $1 a month to help fund my work. $1 might seem a meaningless amount, but if every reader pitched that amount I could work on these articles and their artwork full time. In return, you'll get access to my exclusive Patreon content: regular updates on upcoming books, papers, painting and exhibitions. Plus, you get free stuff - prints, high-quality images for printing, books, competitions - as my way of thanking you for your support. As always, huge thanks to everyone who already sponsors my work!